-

Posts

2,637 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Downloads

Store

Everything posted by Hauksbee

-

It would appear to me that they were near a lake, but not over it. Even if the pilot was over water, that's a long fall and most likely would be fatal.

-

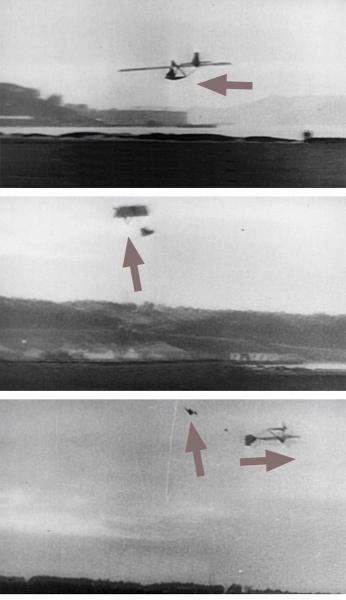

'Was watching a Netflix series on famous feuds in history, (i.e., William Randolph Hearst vs Joseph Pulitzer : newspapers, Steve Jobs vs Bill Gates : computers) and there was a section on the Wright Brothers vs Glenn Curtiss. It was pretty sloppy scholarship, but some interesting film footage. At one point the narrator says that the Wrights were not the first, or only, to try flying. There were others, but the big stumbling block was control of the aircraft; at which point they show a clip that has a glider zooming in from the right, pulls up steeply into a loop and at the top, the plane goes in one direction, and the pilot in another. It was a very dramatic clip but it was not Wright era (or pre-Wright) It looks to me to be a 'Primary Glider' type that was common in flying clubs in 1930's Germany. .

-

The Russian "Night Witches"...

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

A strong case, eloquently stated. Definitely not the turnip-shaped tractor drivers of WW2. -

Verdun, a hundred years on...

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

Aha! I see the difference. Thanks, Olham. -

Verdun, a hundred years on...

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

Is this still a "Fw-190" and not a Ta-152? -

Verdun, a hundred years on...

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

Sweet Jaysus, Olham! If these are Before-and-After pictures, I'm very happy I was not there to see it happen. -

World War I’s Iconic, Ironic Battle By PAUL JANKOWSKI French troops under shellfire during the Battle of Verdun. One hundred years ago, on Feb. 21, 1916, 1,200 German artillery pieces began firing on French positions around Verdun, the ancient fortress town on the Meuse River in eastern France. It was the middle of World War I , and the fighting all along the Western Front that ran between the Channel and the Alps had settled into a static confrontation of men, planes and guns — guns, above all. That day the Germans dropped a million shells onto the forts, forests and ravines around Verdun, and in the 10 months that followed, 60 million more would fall in the area. By then the French had stopped the German advance and even recovered most of the terrain they had lost, reduced by then to a lunar landscape bereft of vegetable or animal life. And 300,000 men had died. What exactly are we commemorating when we gather at the forts, shell-holes and monuments of the former battlefield? We like our battles to have a beginning and an end, to mark a moment and leave a meaning that posterity can grasp and visitors can celebrate — usually, a symbolic or strategic turning point, when one side loses the initiative and never regains it, as at Gettysburg or Stalingrad. We won’t find it at Verdun. The French won a great moral victory — the last, in fact, that their arms would ever achieve — but it did not significantly weaken one side more than the other, alter the strategic picture, or determine the outcome of the war. Verdun declines to boast such significance. There is little to celebrate, and we wander its hills today only as pilgrims to a site of immense suffering. On Sunday an expanded and renovated museum will reopen on the site of one of the ruined villages; later this year, President François Hollande and Chancellor Angela Merkel will inaugurate it officially, and add their names to the long list of dignitaries who came before them. They will say what President François Mitterrand and Chancellor Helmut Kohl said when they visited in 1984 and clasped hands before the great ossuary that holds the shattered remains of the dead — that this must never happen again, that this cannot happen again. They will speak of Europe. French heads of state here once spoke of national unity, of patriotism, of resistance, of heroism. Away from Verdun, authors and survivors wrote of all that and much more. Germans wrote of noble failure, of brave soldiers betrayed by a cynical or inept high command. Some spoke of it in cautionary terms, as a military folly to be avoided at all costs. Never again, wrote one of the architects of the German blitzkrieg of World War II, Heinz Guderian. “I do not want a second Verdun there,” Hitler said of Stalingrad in November 1942, as though to condemn in advance the protracted siege warfare that would cost him his entire Sixth Army. What, the visitor asks, is the meaning of what happened? Like all battlefields, Verdun is silent. Between an older narrative of heroism and a more recent one of pointless slaughter lies an ocean of ambiguity, mingling grandeur with absurdity. Through 1916 French and German losses kept climbing in a macabre pas de deux. Under a sky illuminated by shellfire, in ravines and on hillsides denuded of natural or man-made cover, huddled in what was left of their trenches, the French and Germans lived Verdun in the same way. They used the same words to describe it — “L’Enfer,” “Die Hölle von Verdun” — and spoke too of entering another world, severed from the one they had left behind, and pervaded perhaps by an evil presence. Yes, the French stopped the German offensive on the Meuse. But so what? To a historian 100 years later, Verdun does yield a meaning, in a way a darkly ironic one. Neither Erich von Falkenhayn, the chief of the German General Staff, nor his French counterpart, Joseph Joffre, had ever envisaged a climactic, decisive battle at Verdun. They had attacked and defended with their eyes elsewhere on the front, and had thought of the fight initially as secondary, as ancillary to their wider strategic goals. And then it became a primary affair, self-sustaining and endless. They had aspired to control it. Instead it had controlled them. In that sense Verdun truly was iconic, the symbolic battle of the Great War of 1914-18. Paul Jankowski, a professor of history at Brandeis University, is the author of “Verdun: The Longest Battle of the Great War.”

-

The Russian "Night Witches"...

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

Thanks Olham! Great article. I copied it out and it's now in my 'Archive' file. -

The Russian "Night Witches"...

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

A pity we can't draft them into the BOC. -

The Lethal Soviet Night Witches – Russian Female Heroes Of The Air Few people would connect broomsticks, witches and crop-sprayers to a feared group of female Russian pilots. The women pilots were members of the 588th Night Bomber Regiment of World War II. Even today not many people know about these female pilots who did so much to support their male comrades by the accurate bombing of German troops. These women were usually aged 17 to 26 years of age used to fly on night-time bombing missions. When approaching their target, they would idle their engines and glide into their bombing points. This largely silent approach gave off a “whooshing” sound as they went by, causing the Germans to liken it to the sound of the broomsticks of witches and thus arose the name of “Nachthexen’ – Night Witches! These girl-pilots harassed the Germans to such an extent that they were both hated and feared by them. It was said that any German pilot who managed to bring down one of the planes of a Night Witch would automatically be awarded the Iron Cross. It is no wonder that these intrepid girl-pilots bore the name ‘Night Witches’ with pride! Stalin, after much lobbying by the renowned Russian woman pilot, Marina Raskova, finally allowed a group of females to be trained as bomber pilots and thus created three female units, one of which was the all female 588th Night Bombers Regiment. These female pilots were to be allowed to take the same roles as men who made Russia a very progressive nation. It was the only country at the time to allow women to take part in actual combat missions. Marina Raskova herself began training suitable candidates in flying and navigating and also as maintenance and ground crews. This training of girls as war pilots was seen by the majority of the men in the air force as being of little value, but it was not long before these girl-pilots were to prove their worth and bravery in no uncertain terms. In June of 1941, the German armies attacked Russia (Operation Barbarossa) and moved like lightning across the Russian plains catching Stalin and his armies by surprise. The Nazis devastated the Russian Military, took millions of prisoners and reached the outskirts of Moscow. The situation was critical. The Russians needed all possible manpower and were desperate for pilots and planes – the Germans had to be stopped, at whatever cost or Russia was doomed. The female pilots of the 588th Regiment faced this challenge head on. Their planes – the Policarpov Po-2 bi-panes – were made of plywood and canvas and had mostly been used as crop-dusters, or for training. These planes were small and light and able to carry only two bombs – one under each wing. The crew of two had to fly in an open cockpit, which meant they suffered from frozen feet and frostbite in winter. They were not helped by the fact that they were issued with unsuitable, hand-me-down male uniforms. They had no handguns, no space to carry parachutes and they had to rely on maps and compasses for navigation as they were not equipped with radar. Should they be hit by tracer bullets, their planes would turn into a ball of fire. In spite of these heavy odds these female pilots demonstrated their extreme bravery, often flying 8-10 bombing missions over enemy-held territory, night after night. As these planes were so small and light, the missions were very dangerous. The crews had to search for the German encampments from a very low altitude and so were easy targets, frequently coming back to base with their canvas-covered planes spattered with holes and ripped canvas from being shot up. Sometimes they made it back to base having been set on fire by tracer bullets, often they came home with wounded crew or even worse -they did not return at all. Raskova herself was killed in action. These little Polikarpov biplanes were able to fly very low which helped them to evade the German pilots and since the top speed of these bi-panes was less than the stalling speed of the Nazi planes they were able to manoeuvre more easily and with agility. These features thus formed the only defences the planes had. The Night Witches’ missions usually required that they flew to a nearby target, mostly behind enemy lines. They developed a strategy whereby three planes would fly in formation, and as they neared the target, two planes would fly so as to attract the German searchlights. These two would then fly off in opposite directions, twisting and weaving to avoid the anti-aircraft guns while the third plane would slip quietly through the darkness and drop its bomb load. Something similar would be repeated until all three planes had dropped their bombs before flying back to base where they would refuel, reload and then fly off on their next mission. During heavy fighting, there were as many as 40 planes flying per night. Almost every time these pilots had to fly through a wall of enemy fire. In all, the Night Witches flew approximately 30,000 missions and dropped 23,000 tons of bombs. This constant harassment night after night made the Germans hate the ‘Nachthexen’ even more. The tension was beginning to be felt. They suffered sleepless nights, they felt threatened and unsafe and were wearied by the constant need to be on the alert and to remain in defensive positions. While it caused German morale to fall. The cost to the 588th Night Bombers, was high, for they lost 30 of their pilots. A commander, Nadezha Popover, who completed 852 bombing missions for the Night Bombers, died on the 8th July 2013 at the age of 91. She was quoted as having said “we had a lot of clever, educated, girls “ and “we bombed, we killed, it was part of war.” The cleverness of the ‘Night Witches’ as much as their bravery accounted for their success. Nadezha was one of the 24 Night Witches who were recognized for their incredible determination and bravery against all the odds and who were given the ‘Hero of the Soviet Union’ award. It was a fully deserved honour indeed!

-

Meet the First Black Fighter Pilot...

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

True. And I have read that as time went on, more and more American blacks, encouraged by reports of this acceptance, started pouring in to France whereupon the attitude toward them hardened. -

There seems to have been a lot of that going 'round after the war. Russian soldiers who had spent most of the war in German prison camps were considered 'security risks' and 'tainted' by contact with non-communist ideology. They went to the Gulags. Czech pilots who fled the Nazis, made it to England and flew for the RAF were arrested when they came home.

-

Meet the First Black Fighter Pilot...

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

I agree. The success of the Russian revolution shocked a lot of the western capitalists into cleaning up their act. -

Many Photos of, and around Ernst Udet

Hauksbee replied to Olham's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

Ah yes. You can be skillful. You can be careful. But there's no protection from the utterly random, stray shot.