-

Posts

2,637 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Downloads

Store

Everything posted by Hauksbee

-

Map 11: War and the Railroads

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

Captain, you do provide the most informative footnotes. Thanks. -

Cities Below The Trenches...

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

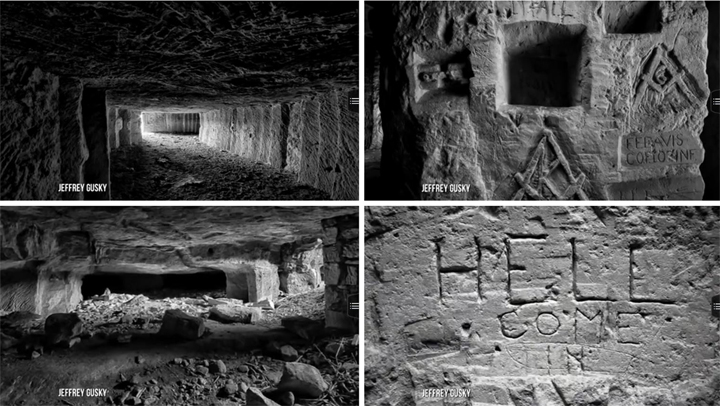

I was stunned by the size of these chambers. Especially the one that went for 18 miles. 'Amazing that they don't get flooded like the trenches themselves. I especially liked the news that the French have carefully preserved them. -

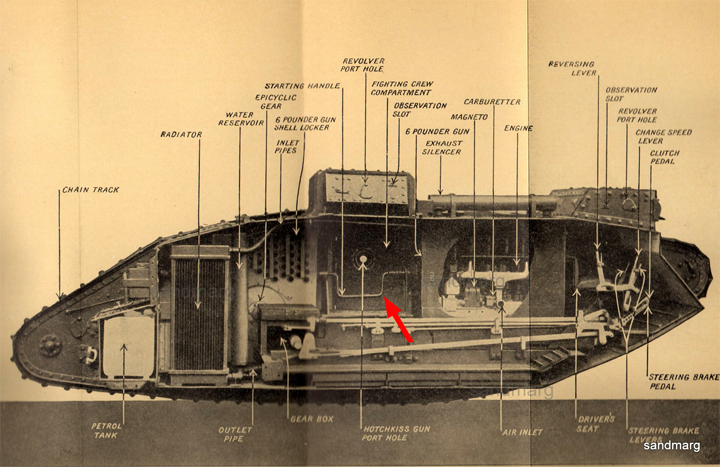

The tank makes its debut The tank, the brainchild of First Lord of the Admiralty (and future Prime Minister) Winston Churchill, was developed by the British during World War I. British officials were anxious not to tip the enemy off to what they hoped would be a powerful new weapon, so they decided to tell people that the strangely-shaped objects they had concealed under tarps were mobile water receptacles: "tanks." [for the desert campaign in Mesopotamia] The code name stuck, and we still call them tanks today. This image shows the design of a tank used by the British at the Battle of Cambrai in 1917. While tanks were developed and used in large numbers by the Allies (and to a much lesser extent by the Germans) they were too primitive to be a major factor in the outcome of the war. Tanks were slow and frequently broke down in the middle of battle. It would take further refinements to turn tanks into the formidable killing machines they would become later in the 20th century. ['love the crank starter handle.]

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m92ZMZL4BI8&ytsession=lo-b5j68bgzEJszGDFPyrmI9zD3Ksudj0aciEJdvfSRqhcBtPYasELf_-bayPDwzfPY2KmFXZO_YvBDTUT1kJAkXlQWP5Oglp39a2ZOaXvAfsLxylkFsd0DWu1rjn2z3TZHbpR07b-aa8WuBWRUGZEDVry3qtyuYxGTSjCgYEpc21elEAjbpQPtCsgAniuF-vclsPPysMOG353fhmU-7WOlUQMTxV1jpxxiknIWm9PPUW6XHvFV-afG2PYEhoAxfnKdqXvBXMS7B4rN_8xqgAOsYpMHAC9SDnzEOt1MzkaObm9C_ihIes5QBrrOlMTL5fZPU8gB0cgvRx1eUEdOPlg Check this one out at ROF/YouTube. Great photography, great action, brilliant editing...and an ending you wouldn't expect.

-

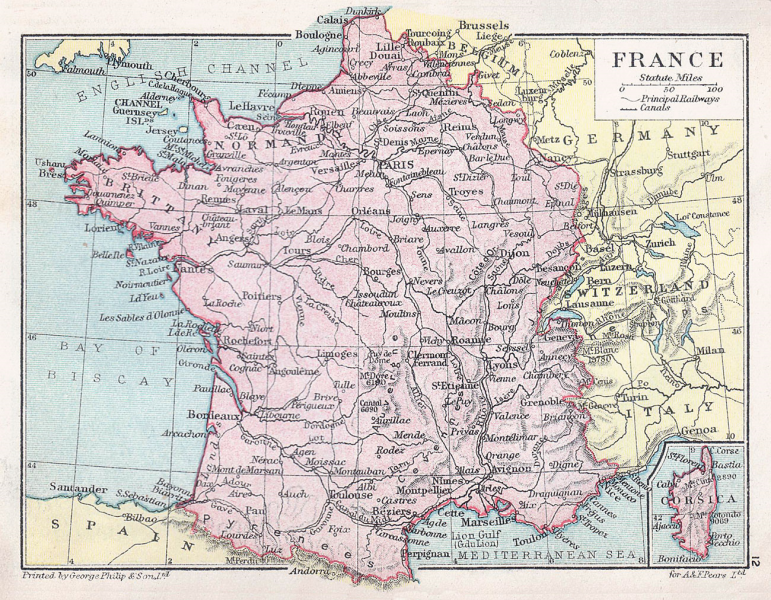

The French rail network in 1914 By 1914, the leading nations of Europe all had extensive rail networks. Trains were hardly a new technology in 1914, but armies relied on them to a greater extent than they ever had before, and this helped to make World War I a bloody war of attrition. In previous wars, armies would clash until one side achieved a breakthrough. At that point, the winning army could encircle the enemy, march on the capital, or take other steps to consolidate their gains and bring the war to an end. The slow speed of transportation meant that reinforcements often couldn't reach the losing side until it was too late to avert disaster. The mature rail networks of the early 20th century changed this dynamic. Now, when one side launched an offensive, the defenders could quickly move thousands of additional troops to counter it. Yet it wasn't practical for attackers who broke through enemy lines to use the enemy's rail lines to move their troops quickly. So defenders were usually more mobile than attackers. This helped to produce the perpetual stalemate of the Western Front (Not one of the more dramatic maps. The blue lines look like rivers, but are the railroads.)

-

http://news.yahoo.com/blogs/power-players-abc-news/beneath-the-trenches--the-secret-world-of-the-great-war-revealed-221659798.html Strange as it may seem, there were vast underground spaces beneath the trenches. Often they were abandoned stone quarries that had been created to build castles. Here's a snippet from the text (but check out the link for the video) “Modern underground cities beneath the trenches, loaded with art, loaded with the infrastructure of modern cities, tens of thousands of men occupying these places at any given time throughout the war,” Gusky said.” “Very often stairways went directly to the trenches, and then they would descend back into safety,” Gusky said. “And there was one place where Americans were where [it] actually wasn't a stairway, it was a slide, and you'd come in and you see not ‘Welcome In,’ but ‘Hell, Come In.’” The underground network of cities, which extended 18 miles long in one place, was constructed from ancient stone quarries that had once been hollowed out to build castles and cathedrals. It was with the stone that soldiers found a means of self-expression, from sketching messages to loved ones to carving complex masterpieces of art. “You see their soul in the art, in the inscriptions,” said Gusky.

-

That makes us both right!

-

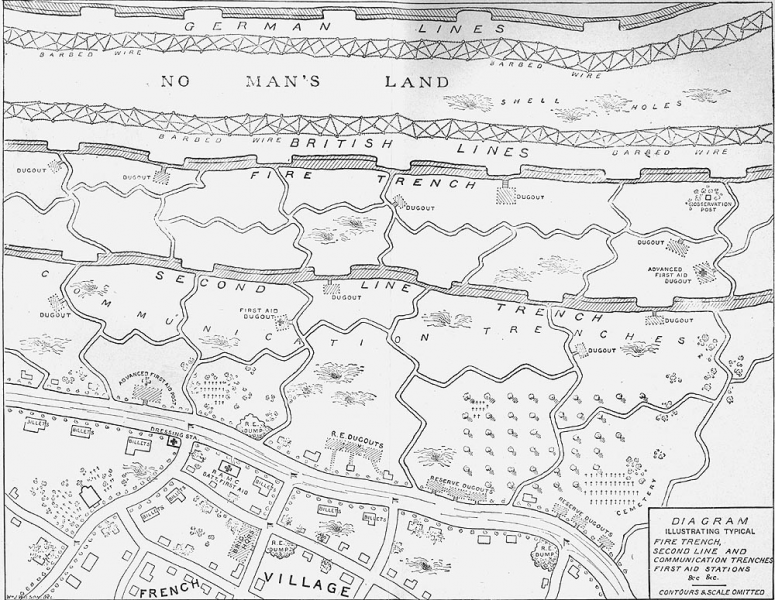

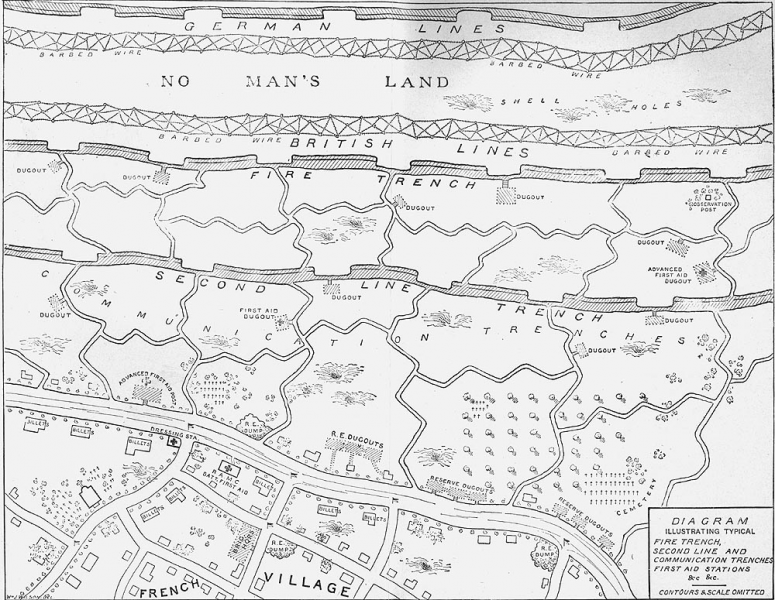

Trench warfare on the Western Front In most military conflicts throughout history, mobility, boldness, and the advantage of surprise are crucial for victory. But World War I began in an unusual period where defensive technologies were often more effective than offensive ones. As a result, the Western Front devolved into a style of trench warfare that would never again be used on such a large scale — the development of tanks and air power had rendered trench warfare much less effective by World War II. This illustration shows the kind of elaborate trench systems that the French, British, and German armies constructed across hundreds of miles of the Western Front. In front of the trenches was barbed wire, an innovation developed in the American West a few decades earlier. It helped slow advancing troops who tried to charge across the no-man's land between the two sides. Then came two lines of wide trenches where soldiers would keep watch; these were connected by narrower trenches used to rotate soldiers in and out of the front lines. Further back were trenches for communications, first aid, and the storage of supplies. At the very back would be the artillery, guns powerful enough to send massive shells deep into enemy lines. Poor sanitation, constant shelling, and the lack of adequate shelter made life miserable for soldiers who had to endure life in the trenches.

-

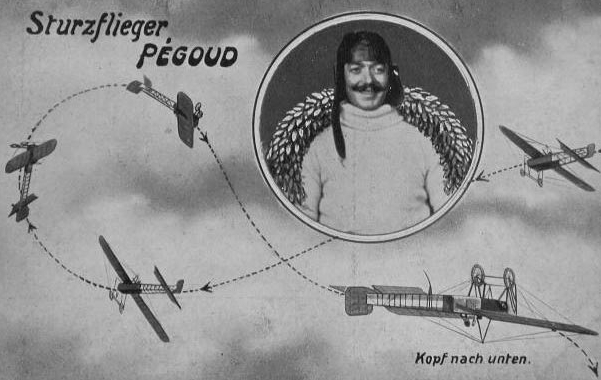

Found this while looking for something else. [serendipity] It's a German post card celebrating Alphonse Pegoud's being the first person to do a loop. (pretty bold being in a Bleriot) In fact, a Russian pilot was the first. By 12 days. 'Guess news didn't travel so fast in those days.

-

Air Department Sparrow - 1915 The AD Scout (later known as the Sparrow) was designed by Harris Booth of the British Admiralty's Air Department as a fighter aircraft to defend Britain from Zeppelin bombers during World War I. This aircraft was an unconventional heavily-staggered, single-bay biplane, built to meet an Admiralty requirement for a fighter built from commercially obtainable materials and which could be armed with the Davis two-pounder quick-fire recoilless gun. The gun was mounted in the bottom of a short, single-seat nacelle, the top longerons were bolted directly to the main spars of the upper wing. The A.D. Scout was powered by a 100 hp Gnôme Monosoupape rotary engine driving a 9 ft pusher airscrew. The pilot had a excellent view in nearly every direction. A twin-rudder tail was attached by four booms, and it was provided with an extremely narrow-track "pogo stick" type undercarriage. Four prototype aircraft were ordered in 1915. Two aircraft, (serial numbers 1452 and 1453) built by Hewlett and Blondeau Ltd of Leagrave, Beds. The remaining two (serial numbers 1536 and 1537) were built by Blackburn Aeroplane & Motor Company. The four prototypes were all delivered to RNAS Chingford. The test trials flown by pilots of the Royal Naval Air Service were less than favorable. They proved the aircraft to be seriously overweight, fragile, sluggish, and difficult to handle, even on the ground. Due to the fact the Sparrow was considerably over-weight and difficult to handle in the air, all of the examples were scrapped.

-

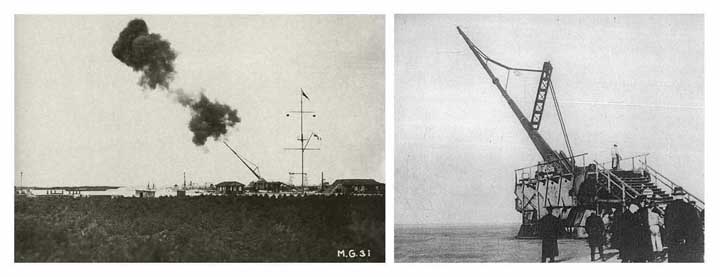

The text with this installment was pretty bland, so I did a Wiki search and found some really interesting facts about these Super Guns. The Paris Gun (German: Paris-Geschütz) was the name given to a type of German long-range siege gun, several of which were used to bombard Paris during World War I. They were in service from March to August 1918. When first employed, Parisians believed they had been bombed by a high-altitude Zeppelin, as neither the sound of an airplane nor a gun could be heard. They were the largest pieces of artillery used during the war by barrel length if not caliber, and are considered to be superguns. The Paris Guns hold a significant place in the history of astronautics, as their shells were the first man-made objects to reach the stratosphere. Also called the "Kaiser Wilhelm Geschütz" ("Emperor William Gun"), they were often confused with Big Bertha, the German howitzer used against the Liège forts in 1914; indeed, the French called them by this name, as well. They were also confused with the smaller "Langer Max" (Long Max) cannon, from which they were derived; although the famous Krupp-family artillery makers produced all these guns, the resemblance ended there. As military weapons, the Paris Guns were not a great success: the payload was minuscule, the barrel required frequent replacement and its accuracy was only good enough for city-sized targets. The German objective was to build a psychological weapon to attack the morale of the Parisians, not to destroy the city itself. The Paris Gun was a weapon like no other, but its capabilities are not known with full certainty. This is due to the weapon's apparent total destruction by the Germans in the face of the Allied offensive. Figures stated for the weapon's size, range, and performance varied widely depending on the source — not even the number of shells fired is certain. With the discovery (in the 1980s) and publication (in the Bull and Murphy book) of a long note on the gun written shortly before his death in 1926 by Dr. Fritz Rausenberger, who was in charge of its development at Krupp, the details of its design and capabilities were considerably clarified. The gun was capable of firing a 106-kilogram (234 lb) shell to a range of 130 kilometers (81 mi) and a maximum altitude of 42.3 kilometers (26.3 mi) — the greatest height reached by a human-made projectile until the first successful V-2 flight test in October 1942. At the start of its 182-second trajectory, each shell from the Paris Gun reached a speed of 1,640 meters per second (5,400 ft/s). Seven barrels were constructed. They used worn–out 38 cm SK L/45 "Max" gun barrels that were fitted with an internal tube that reduced the caliber from 380 millimeters (15 in) to 210 millimeters (8 in). [A large surprise to me. I had always felt that an enormous gun fired an enormous shell. In reality, it fired a modest shell a very long way. Hauksbee] The tube was 21 meters (69 ft) long and projected 3.9 meters (13 ft) out of the end of the gun, so an extension was bolted to the old gun-muzzle to cover and reinforce the lining tube. A further, 12-meter long smooth–bore extension was attached to the end of this, giving a total barrel length of 34 meters (112 ft). This smooth section was intended to improve accuracy and reduce the dispersion of the shells, as it reduced the slight yaw a shell might have immediately after leaving the gun barrel, that is produced by the gun's rifling. The barrel was braced to counteract barrel droop due to its length and weight, and vibrations while firing; it was mounted on a special rail-transportable carriage and fired from a prepared, concrete emplacement with a turntable. The original breech of the old 38 cm gun did not require modification or reinforcement. Since it was based on a naval weapon, the gun was manned by a crew of 80 Imperial Navy sailors under the command of Vice-Admiral Rogge, chief of the Ordnance branch of the Admiralty. It was surrounded by several batteries of standard army artillery to create a "noise-screen" chorus around the big gun so that it could not be located by French and British spotters. The projectile was the first human-made object to reach the stratosphere. The historian Adam Hochschild put it this way: "It took about three minutes for each giant shell to cover the distance to the city, climbing to an altitude of 25 miles at the top of its trajectory. This was by far the highest point ever reached by a man-made object, so high that gunners, in calculating where the shells would land, had to take into account the rotation of the Earth. [This made gun-laying Tables so complex that it spurred the development of mechanical computers. Hauksbee] For the first time in warfare, deadly projectiles rained down on civilians from the stratosphere." This reduced drag from air resistance, allowing the shell to achieve a range of over 130 kilometres (81 mi). The Paris Gun was the largest gun built at the time, but it was surpassed by the Schwerer Gustav of World War 2. This fired shells up to 70 times heavier, but with only around half the muzzle velocity and less than one third the range. The Paris Gun shells weighed 106 kg (234 lb). The shells initially used had a diameter of 216 mm (8.5 in) and a length of 960 mm (38 in). The main body of the shell was composed of thick steel, containing 7 kg (15 lb) of TNT. The small amount of explosive – around 6.6% of the weight of the shell – meant that the effect of its shellburst was small for the shell's size. The thickness of the shell casing, to withstand the forces of firing, meant that shells would explode into a comparatively small number of large fragments, limiting their destructive effect. A crater produced by a shell falling in the Tuileries Garden was described by an eye–witness as being 10 to 12 ft (3.0 to 3.7 m) across and 4 ft (1.2 m) deep. The shells were propelled at such a high velocity that each successive shot wore away a considerable amount of steel from the rifled bore. Each shell was sequentially numbered according to its increasing diameter, and had to be fired in numeric order, lest the projectile lodge in the bore, and the gun explode. Also, when the shell was rammed into the gun, the chamber was precisely measured to determine the difference in its length: a few inches off would cause a great variance in the velocity, and with it, the range. Then, with the variance determined, the additional quantity of propellant was calculated, and its measure taken from a special car and added to the regular charge. After 65 rounds had been fired, each of progressively larger caliber to allow for wear, the barrel was sent back to Krupp and rebored to a caliber of 238 mm (9.4 in) with a new set of shells. The shell's explosive was contained in two compartments, separated by a wall. This strengthened the shell and supported the explosive charge under the acceleration of firing. One of the shell's two fuses was mounted in the wall, with the other in the base of the shell. The shell's nose was fitted with a streamlined, lightweight, ballistic cap – a highly unusual feature for the time – and the side had grooves that engaged with the rifling of the gun barrel, spinning the shell as it was fired so its flight was stable. Two copper driving bands provided a gas-tight seal against the gun barrel during firing. The Paris gun emplacement was dug out of the north side of the wooded hill at Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique. The gun was mounted on heavy steel rails embedded in concrete, facing Paris. The Paris gun was used to shell Paris at a range of 120 km (75 mi). The distance was so far that the Coriolis effect — the rotation of the Earth — was substantial enough to affect trajectory calculations. The gun was fired at an azimuth of 232 degrees (west-southwest) from Crépy-en-Laon, which was at a latitude of 49.5 degrees North. The gun was fired from the forest of Coucy and the first shell landed at 7:18 a.m. on 21 March 1918 on the Quai de la Seine, the explosion being heard across the city. Shells continued to land at 15 minute intervals, with 21 counted on the first day. The initial assumption was these were bombs dropped from an airplane or Zeppelin flying too high to be seen or heard. But within a few hours, sufficient casing fragments had been collected to show that the explosions were the result of shells, not bombs. By the end of the day, military authorities were aware the shells were being fired from behind German lines by a new long-range gun, although there was initially wild press speculation on the origin of the shells. This included the theory they were being fired by German agents close by Paris, or even within the city itself, so abandoned quarries close to the city were searched for a hidden gun. However, the actual gun was found within days by the French air reconnaissance aviator Didier Daurat. A total of around 320 to 367 shells were fired, at a maximum rate of around 20 per day. The shells killed 250 people and wounded 620, and caused considerable damage to property. The worst incident was on 29 March 1918, when a single shell hit the roof of the St-Gervais-et-St-Protais Church, collapsing the entire roof on to the congregation then hearing the Good Friday service. A total of 91 people were killed and 68 were wounded. The gun was taken back to Germany in August 1918 as Allied advances threatened its security. The gun was never captured by the Allies. It is believed that near the end of the war it was completely destroyed by the Germans. One spare mounting was captured by American troops near Château-Thierry, but the gun was never found; the construction plans seem to have been destroyed as well. In the 1930s, the German Army became interested in rockets for long range artillery as a replacement for the Paris Gun—which was specifically banned under the Versailles Treaty. This work would eventually lead to the V-2 rocket that was used in World War 2.

-

OT--Anybody Know What This Is?

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

Quite so. After a quick Google search, it seems that the "Funnies" were designed to assault beaches (Normandy) and were adaptations built onto existing tanks, i.e., the Matilda. That German monster has "klunky" written all over it, and, no doubt, carried a sign that said "Shoot here first!" I've always felt the cleverest mine-clearing device was the "Flail Tank" It didn't depend on great weight or huge rollers. -

OT--Anybody Know What This Is?

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

Thanks, Stratos. It's nice to have that settled. I was leaning toward the 'fake' Luft '46 opinion. Here's two pics culled from the link Stratos posted. Accompanying text (last paragraph) had this to say about it: During the trial tests, it proved that this vehicle was unsuited to the operations of modern mechanized warfare. Its ponderous weight, slow speed, and its awkward size made the Minenräumer (minesweeper) a large target for opposing artillery and the project was thus abandoned. -

Among the topics covered in "WWI In 40 Maps" is the German 'Super Guns'; the best known being the 'Paris Gun', [spoiler alert: It wasn't called "Big bertha"]. I started poking around on-line and tucked among a Yahoo Image Search [e.g., Paris Gun clones, huge Siege Mortars and humongous WWII tanks] I found this odd-ball. 'Never seen its like before. Anybody know what it is? Is it even real?

-

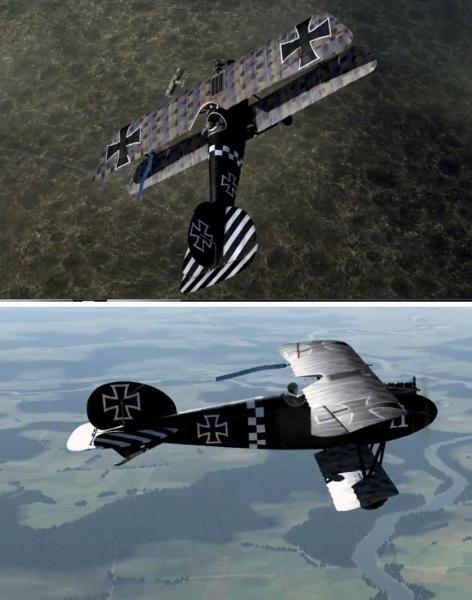

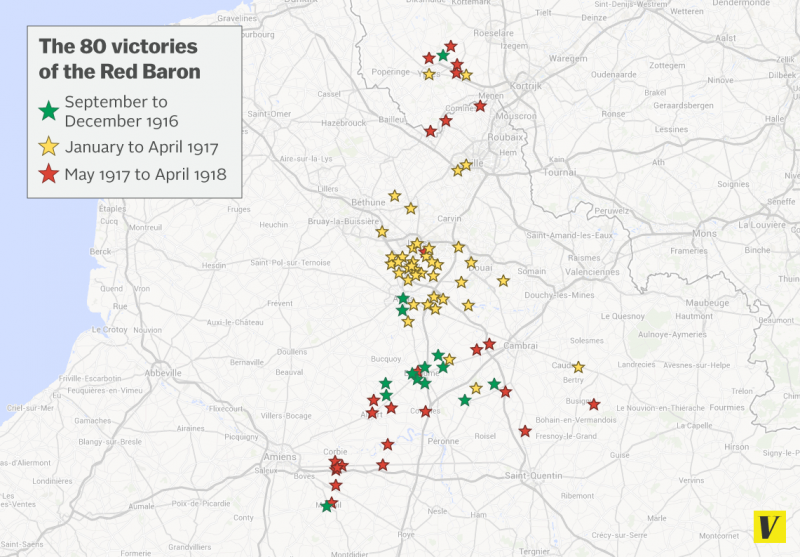

The 80 victories of the Red Baron [This article, for reasons unknown, stopped abruptly after von Richtofen's first crash in a Halberstadt D.II, so I consulted Wikipedia and fleshed out the story. The original article is in red. Olham: I know that the 'von' in von Richtofen is usually in lower case, but how is it handled when the name is at the beginning of the sentence?] World War I was the first war to see large-scale use of airplanes. At first, they were primarily used for reconnaissance, but both sides increasingly used them for offensive purposes as well. As airplanes dropped bombs on enemy cities in growing numbers, countries started looking for ways to shoot enemy airplanes out of the sky. A key innovation was the synchronization gear, which allowed pilots to fire a gun through a spinning propeller without damaging the blades. This created a new class of fighter airplanes, and a new class of pilots to fly them. The most famous of these "flying aces" was the German pilot Manfred von Richthofen. von Richthofen was a Freiherr (literally "Free Lord"), a title of nobility often translated as Baron. This is not a given name nor strictly a hereditary title—since all male members of the family were entitled to it, even during the lifetime of their father. This title, combined with the fact that he had his aircraft painted red, led to von Richthofen being called "The Red Baron" ("der Rote Baron" both inside and outside Germany. During his lifetime, however, he was more often described in German as Der Rote Kampfflieger (variously translated as "The Red Battle Flyer" or "The Red Fighter Pilot"). This name was used as the title of von Richthofen's 1917 autobiography. Between 1916 and 1918, he achieved 80 victories over enemy aircraft, the highest of any pilot in the war. The Red Baron became a celebrity on both sides of the front line and his victories provided a boost to German morale. After downing 21 enemy planes in April 1917, he was in a crash in July. He was flying his Halberstadt D.II when, on 6 March, in combat with F.E.8s of 40 Squadron RFC, his aircraft was shot through the fuel tank, probably by Edwin Benbow, who was credited with the victory. von Richthofen was able on this occasion to force land without his aircraft catching fire. von Richthofen then scored a victory in the Albatros D.II on 9 March, but since his Albatros D.III was grounded for the rest of the month, von Richthofen switched again to a Halberstadt D.II. He returned to his Albatros D.III on 2 April 1917 and scored 22 victories in it before switching to the Albatros D.V in late June. From late July, following his discharge from hospital, von Richthofen flew the celebrated Fokker Dr.I triplane, the distinctive three-winged aircraft with which he is most commonly associated, although he did not use the type exclusively until after it was reissued with strengthened wings in November. von Richthofen was a brilliant tactician, building on Boelcke's tactics. Unlike Boelcke, he led by example and force of will rather than by inspiration. He was often described as distant, unemotional, and rather humourless, though some colleagues contended otherwise. He circulated to his pilots the basic rule which he wanted them to fight by: "Aim for the man and don't miss him. If you are fighting a two-seater, get the observer first; until you have silenced the gun, don't bother about the pilot". Although he was now performing the duties of a lieutenant colonel (in modern RAF terms, a wing commander), he remained a captain. The system in the British army would have been for him to have held the rank appropriate to his level of command (if only on a temporary basis) even if he had not been formally promoted. In the German army, it was not unusual for a wartime officer to hold a lower rank than his duties implied, German officers being promoted according to a schedule and not by battlefield promotion. For instance, Erwin Rommel commanded an infantry battalion as a captain in 1917 and 1918. It was also the custom for a son not to hold a higher rank than his father, and von Richthofen's father was a reserve major. On 6 July 1917, during combat with a formation of F.E.2d two seat fighters of No. 20 Squadron RFC, near Wervicq, von Richthofen sustained a serious head-wound, causing instant disorientation and temporary partial blindness. He regained consciousness in time to ease the aircraft out of a free-falling spin and executed a rough landing in a field within friendly territory. The injury required multiple surgical operations to remove bone splinters from the impact area. The air victory was credited to Captain Donald Cunnell of No. 20, who was himself shot down and killed a few days later (by anti-aircraft fire). The Red Baron returned to active service (against doctor's orders) on 25 July, but went on convalescent leave from 5 September to 23 October. His wound is thought to have caused lasting damage (he later often suffered from post-flight nausea and headaches) as well as a change in temperament. There is even a theory linking this injury with his eventual death. von Richthofen received a fatal wound just after 11:00 am on 21 April 1918, while flying over Morlancourt Ridge, near the Somme River. At the time, the Baron had been pursuing (at very low altitude) a Sopwith Camel piloted by a novice Canadian pilot, Lieutenant Wilfrid "Wop" May of No. 209 Squadron, Royal Air Force. In turn, the Baron was spotted and briefly attacked by a Camel piloted by a school friend (and flight commander) of May's, Canadian Captain Arthur "Roy" Brown, who had to dive steeply at very high speed to intervene, and then had to climb steeply to avoid hitting the ground. von Richthofen turned to avoid this attack, and then resumed his pursuit of May. It was almost certainly during this final stage in his pursuit of May that a single .303 bullet hit von Richthofen, damaging his heart and lungs so severely that it must have caused a very quick death. In the last seconds of his life, he managed to make a hasty but controlled landing in a field on a hill near the Bray-Corbie road, just north of the village of Vaux-sur-Somme, in a sector controlled by the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). One witness, Gunner George Ridgway, stated that when he and other Australian soldiers reached the aircraft, von Richthofen was still alive but died moments later. Another eye witness, Sergeant Ted Smout of the Australian Medical Corps, reported that von Richthofen's last word was "kaputt".

-

Thanks Olham. I just looked at the 40 maps I saved to a folder on my desktop. It seems as though they mis-numbered some, so, as I count down from 40, the last map may not be #1, Also the maps were broken out into 5 categories: (1) Background to WWI, (2) European Battles, (3) The War Outside Europe, (4) Technology of WWI and (5) Allied Victory. We're just starting on (4) Technology. Wherein I discover an installment on Trenches with this very same map. So we'll get to see it again with text. Stay tuned.

-

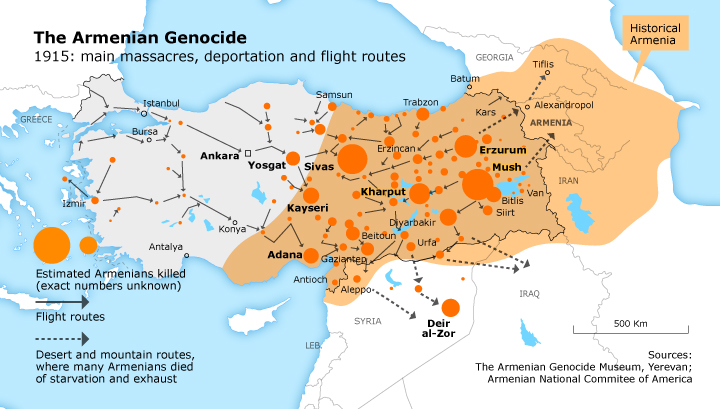

Ottoman Turks commit genocide against the Armenians In 1915, frustrated by early setbacks in the war, leaders of the Muslim-majority Ottoman empire launched a campaign to purge non-Muslim elements. They began persecuting the Armenians, a Christian ethnic group whose ancestral homeland straddled the border between the Russian and Ottoman empires. Hundreds of thousands of Armenian men, women, and children were slaughtered. According to some estimates, as many as three quarters of the 2 million Armenians in the Ottoman Empire were killed. Hundreds of thousands of Armenians fled their homeland, producing significant Armenian diaspora populations in the United States, Russia, and elsewhere. No one was punished for these atrocities, and to this day it's a sensitive topic for the Turkish government. As recently as 2007, diplomatic pressure from Turkey dissuaded Congress from officially recognizing the incident as a genocide.

-

- 1

-

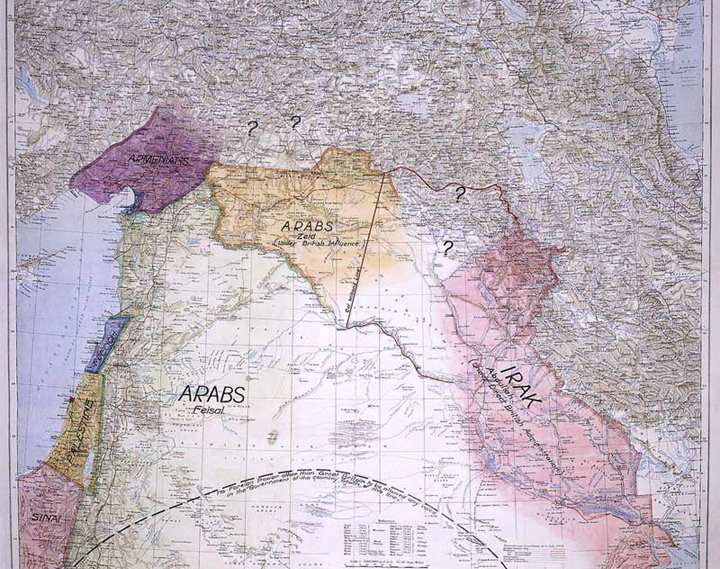

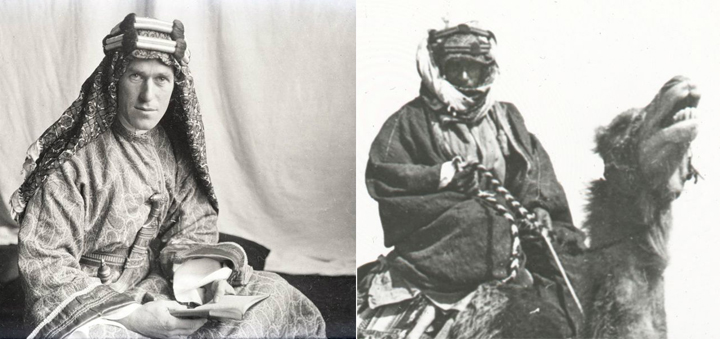

-

Lawrence of Arabia and Britain's betrayal of Arab allies One of the most remarkable figures of World War I was TE Lawrence, whose exploits in the Middle East were immortalized in the 1962 movie Lawrence of Arabia. Before the war, Lawrence was an archeologist, and he got to know the Middle East during expeditions to the region. When war broke out, the British recruited him to help organize an Arab revolt against the Ottoman empire. His pre-war connections made him particularly effective in this role. He fought alongside the Arabs in a series of battles between 1916 and 1918. At the end of the war in November 1918, Lawrence presented this map to his superiors in Britain, showing proposed borders for a postwar Middle East. The British had promised independence to Arab Allies who participated in the rebellion, and Lawrence attended the 1919 Paris Peace Conference to press for these promises to be kept. Instead, the British and French divided Arab territories under the terms of the Sykes–Picot Agreement (discussed below), which they had secretly negotiated in 1916.

- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

-

It's not an F-16 engine, but his heart's in the right place...

-

The Goetzen and "The African Queen"

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

That could be it. There's scaffolding built up the hull, so work is being done on the outside. And it's rickety-looking. Good enough to hold a paint crew, but not heavy work. -

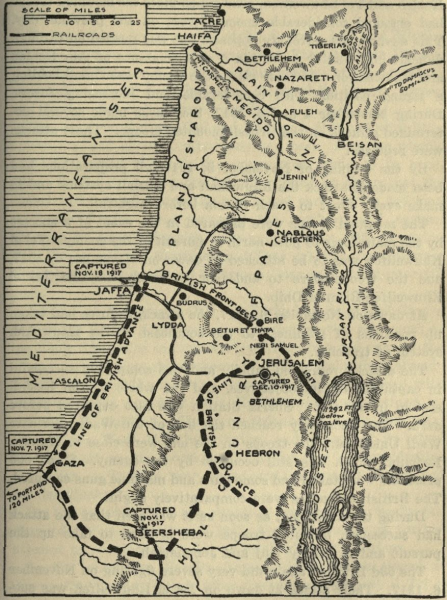

Britain conquers Palestine After the failure of the Gallipoli campaign in 1916, Allied forces regrouped in Egypt and began making plans to take Ottoman-held land in the Levant. This map shows part of that effort, Britain's successful 1917 campaign in Palestine. The British invasion of Palestine would have long-lasting consequences. On November 2, 1917, British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour wrote a letter endorsing "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people." Balfour cautioned that "nothing shall be done that may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine." In 1922, the League of Nations officially endorsed British administration of Palestine. British policies after World War I helped lay the groundwork for the eventual UN partition of Palestine between Arab and Jewish states — and everything that followed from that. For a great film about the Battle for Beersheba, check out the Australian film "The Light Horsemen" [Hauksbee]

-

The Goetzen and "The African Queen"

Hauksbee replied to Hauksbee's topic in WOFF UE/PE - General Discussion

The text of the article said "after having her engines thoroughly greased..." and she was scuttled before capture. My first thought was that it's some kind of freshwater barnacle-type critter. But each round spot seems to have a dark center. Might it be paint blistering away from the rivet head after being submerged for so long? -

In America, especially California, the 'impossible' is just a starting point.

-

I've seen a few variations on this idea. I can only find two right now.