-

Content count

147 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Calendar

Gallery

Downloads

Store

Everything posted by Raine

-

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion

Journal of FCdr Douglas Bell-Gordon, RNAS Part 21 12 September 1917. Leffrinckoucke, France. " I maintained a height advantage over the two giant machines I had selected and planned to approach them from their starboard quarter." Day one back in France and I have finally summonsed up the energy to bring my journal up to date. It has been a splendid summer. Some of the energy and joy of life has returned and I am even looking forward to my first patrols over the lines. Following my brief hospital stay in June, I returned to Dover and immersed myself in the organisation of my little unit. Munro had done a brilliant job in my absence and the general standard of cleanliness and organisation had continued to improve. We still had only two Camels, although our overall effectiveness was improved when the ancient Bristols were replaced by Sopwith Pups. On 4 July, we received a telephone warning that enemy aircraft were heading for the coast north of the Thames. At the sheds, I gave the orders to get airborne as quickly as possible and to proceed individually on a course that would bring us over Manston and thence north to Harwich. We got all six serviceable machines on their way within five minutes. Thick clouds covered much of southeast England. I chose a gap a little off to the north-east and climbed through the cloud layer into brilliant sunlight. With the ground now out of sight, I changed course over what I can only assume to be Manston. Some time later the sky cleared enough for me to see Margate disappearing under my tail. The time over water seemed interminable. As I approached land on the northern side of the Thames Estuary, the clouds became heavier. I patrolled for a half hour between Southend and Felixstowe before Munro spotted me and joined up. When my petrol gauge told me it was nearly time to head home, I led the pair of us back below the cloud and into a driving drizzle. There was no sign of the Hun lower down and we returned to Dover. Three days later we abandoned our breakfast to fly in a rainstorm up to Southend. Returned after more than two hours wet and hungry without seeing a thing once again. On 22 July 1917, we again chased rumours of Gothas, this time up to Margate. A beautiful morning – the lanes and fields and corpses of Kent spread out beneath us in a tapestry of green and yellow that spoke of everything English. Smoke curled from the occasional chimney above thatched cottage roofs. White dots were scattered about fields where sheep grazed. In the river valleys, wisps of fog hung beneath the crowns of oak trees. I found myself humming “Hearts of Oak” as I climbed to 10,000 feet. We spotted the Huns making landfall over Sandwich Bay. There were perhaps sixteen Gothas in a long gaggle of twos and threes. They shone silver in the sunlight and were probably rather pretty. By this point, however, I was thoroughly upset at the idea that they could come here and drop bombs on this island paradise. I recall chuckling to myself that it was strange for me as a Canadian to be thinking of it as our island and smiling at the idea of my parents hearing this. Both were born in Scotland and would have been proud of my sentiment. After my experience in June when the rear gunner of the Gotha nearly did me in, I resolved to approach these Huns differently. I maintained a height advantage over the two giant machines I had selected and planned to approach them from their starboard quarter. At the right moment I banked and began a shallow dive, firing from 350 yards until I swooped beneath the nearest Gotha. But by the time I zoomed and turned back for a second pass they were well off. I chased them and narrowed the distance, this time firing from long range. The rear gunners of both Gothas converged their fire on me and forced me to break off the attack. Now the Huns dropped their bombs randomly. Many fell over water. Then they turned east and ran for Belgium. I noticed one of the giant bombers fall out of formation and tumble downwards. To my joy, I saw Munro returning from that direction. His was our first victory over these intruders. At the end of July, I was granted a few days’ leave and took the train north to Glasgow to visit my Uncle Bill and Auntie Tilda. Uncle Bill is my father’s younger brother. Like Pop, he is a policeman. Glasgow was far more industrialised than I expected, or at least it seemed that way because of the way that years of soot had stained every building. Bill and Tilda live in Whiteinch, a pleasant part of the city with some lovely green spaces, although I suspect even the leaves of the trees were a shade darker than they should have been. Bill called it a “hard toun” in his broad Scots dialect. The people of Glasgow were friendly and funny, yet even their humour had a hard edge. Uncle Bill related the story of being on patrol when an electric bell sounded. Three young hoodlums had thrown a brick through a shop window and made off with some jewellery. Bill blew his whistle and gave chase. As the louts reached the next street they ran past a one-legged man with a crutch coming the other way. “Only in Glesga,” Bill said while giggling uncontrollably, “wid the buggers pause in their flight tae kick the crutch frae under a cripple!” I arrived back at Dover on 9 August to find a familiar face. Gerry Hervey had been drafted from Naval 8 to join our little crew. We had a jolly reunion and I was delighted to welcome my fellow Canadian to the flight. Even more interesting, Gerry was able to bring me up to date with events after my departure from France. It seems that the Evening News thought it best to check with the authorities before printing Huntington’s fantastic account of scrapping with the Red Baron. This resulted in his being “invited” to a meeting at Fleet HQ in Dunkirk. The story that made it back to the squadron was that Huntington was given his own command and would not be returning to Naval 8. His exploits with von Richthofen never did appear in the paper. According to Hervey, Huntington is now a course commander at White City, the training centre in west London where RNAS probationary sublieutenants are taught drill, which fork to use, and Traditions of the Service. He’s the man for the job, I’m sure. We launched the entire flight on the morning of 12 August. There were reports of Gothas heading toward the Thames and so we were to patrol from Southend nearly as far as Harwich. Munro and I led the way in our Camels, while Hervey led the others trailing behind in their Pups. Arriving at 12,000 feet south of Clacton, Munro and I immediately spotted fifteen or twenty of the large bombers inbound from the open water. I picked a group of three Huns and signalled that I would take the closest. We approached from their starboard beam, firing long bursts and diving away out of range before zooming to attack from the opposite beam. My rounds splashed along the wings and around the starboard engine. As I turned, the Gotha began to trail a thin stream of smoke or vapour and fell out of formation. This was no time for caution. I chased after it, ignoring the tracer from the bomber’s rear gunner. Another long burst sent the Hun tumbling out of control. Two flailing bodies detached themselves from the following machine. Only the pilot stayed with the aircraft all the way down until it crashed into the water about four miles southwest of Clacton. I saw another Gotha turning eastward and gave chase. Several long bursts exhausted my ammunition. Although the Hun lost altitude, it did not fall – at least I could not say so with certainty. We had ten days of quiet until 22 August. On that day we intercepted another large group of German machines as they crossed the coast near Manston. This time they turned back as soon as we engaged. I fired it one of the fleeing Gothas which seemed to lose control but I lost it in clouds below. The enemy machine was not seen to crash and was considered only to have been driven off. Most distressingly, however, I learned on landing that Munro had put down at Manston with a serious wound to his thigh. They took him to the Royal Seabathing Hospital in Margate. I borrowed a car to go there that evening. By the time I arrived, Munro was dead from his wound. For the rest of the month, the Germans left us alone. Two more Camels arrived and we focused on getting everyone in the flight some time on these difficult machines. The Camel demands full right rudder during the takeoff roll. Pilots who did not take this instruction seriously would find themselves swerving off-line dramatically and could easily dip a wingtip onto the field. Next, pilots need to avoid right-hand turns on takeoff. Those who ignore this caution frequently induce a tight spin close to the ground. In left-hand turns the Camel wants to point its nose up and without firm left rudder will stall. Finally, the machine is slightly tail-heavy. Constant forward pressure on the stick is needed to fly level. Low flying takes practice. On 11 September 1917, everything changed. I was called to Wing and given orders to report to Number 9 (N) Squadron, currently based at Leffrinckoucke, a field on the eastern edge of Dunkirk. There I was told to report to Squadron Commander Vernon as a Flight Commander – a substantive one as opposed to “acting”! The following day – this morning – I sailed from Folkestone to Dunkirk aboard HMS Greyhound. This little destroyer was showing its age as it was quite overcome by the stiff wind and moderate seas. I joined several other flying officers as guests of the captain on the bridge of the ship. After only fifteen minutes of clutching the binnacle as we heaved and tossed, I decided to leave their company and the captain’s pipe smoke behind and head aft to check on the stern rails and stare at the horizon for a good while. It was a blessing finally to disembark and get safely back to the war. Leffrinckoucke is not much of an aerodrome. The field is featureless except for several Armstrong huts (a pilots’ room, a cramped mess for the lower deck, and an office) and two long rows of Bessonneaux. I was surprised to see a group of several dozen Chinese labourers preparing a site for accommodations huts. The pilots and most of the chiefs and petty officers are currently billeted nearby, while the ratings are mainly under canvas. Squadron Commander Vernon welcomed me generously and walked me about the place. He explained that he had been here less than two months. The squadron had been somewhat written off by General Trenchard, GOC of the Flying Corps – not aggressive enough and with a poor record for equipment maintenance and reliability. We share the aerodrome with 54 Squadron RFC. They are a Sopwith Pup group and have a good reputation. There is a dinner at a hotel nearby tonight and we will be together with them. I had a chance this afternoon to have tea with the Boucher family in whose house I am billeted along with two other officers, Flight Commander Joe Fall from the Yukon and Flight Sublieutenant Roy Brown from near Ottawa. I’m told about half of the squadron is Canadian. Over tea and biscuits with them and the elderly Monsieur et Madame Boucher, we discussed the need for a heavily Canadian squadron to set a better example. More to follow… -

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion

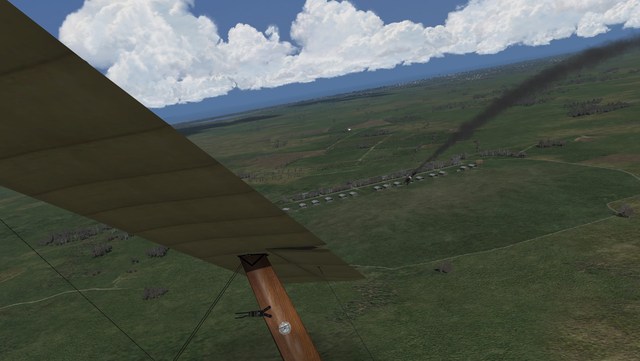

Journal of FLt Douglas Bell-Gordon, RNAS Part 20 14 June 1917. Manor House Hospital, Folkestone. "Wave upon wave of giant aircraft were approaching the coast east of Margate. I estimated at least fifteen or twenty Gothas." Early May 1917 – Farewell to Naval Eight It has been so long since I last picked up this journal that I must return to what seems a distant past. My last entry followed an awkward conversation with squadron commander Bromet on 3 May 1917. Later that evening, Soar and Simpson showed up at the estaminet in Auchel. “Here’s the drill,” I began after pouring double brandies for each of us. “We’re going to write two letters that will bring the whole romance between Huntington and Apollonia to an end. I spoke with D’Albiac just before heading out for town and I have reason to believe that the skipper wants to separate Huntington and me and will be shipping me off to a training job, or a defence flight, or a seaplane squadron. So that’s get this done. The first letter is from our Miss Willing to the editor of the Evening News…” My two friends sat back in their chairs looking at me open-mouthed, as if I were mad. “Reggie, let me rattle on and you take notes. I’ll do it all up in Apollonia’s hand later. For now, let’s get our ideas down.” I paused, took a deep breath, and began. “Dear Sir, We have all followed with horrifying interest the reports from France and Flanders of the vicious struggles with the enemy on the ground and in the air. It is with regard to the latter that I write you this evening. Several recent articles have mentioned the ferocity of the enemy’s military aviation and have singled out a pilot named von Richthofen as the premier German flyer. To read what has been written, one would think that the enemy dominates our own valiant boys, none of whom rise to the level of this Prussian, a level deserving of widespread renown. I believe that our newspapers are allowing a great disservice to be done to the men of the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service. “A while ago I entered into a friendly correspondence with Flight Lieutenant H, an officer with the Royal Navy’s air service who is currently at the front in France. I am enclosing several pages from a letter this brave fellow sent me not long ago. As you will see, he has destroyed on his own nearly thirty enemy machines in the air despite having been in France only a few months. Furthermore, in these pages he describes an encounter with an enemy aeroplane almost certainly piloted by the vaunted von Richthofen himself. Flight Lieutenant H fought that beastly Hun to a standstill and was saluted by him in the air before the fight ended. THIS is what our British aviators are capable of doing! Why are their stories not told? Why cannot we have our own heroes when those men richly deserve our recognition. I pray that you will see the wisdom in publishing Flight Lieutenant H’s account of his exploits and redress this sad situation. Sincerely, A.W., Torquay.” “Would they publish this?” asked Simpson. “Damned if I know for sure,” I said, “but I’ll bet on.” Reggie chuckled to himself. “If this appears in the paper, our boy Huntington will be doing the hatless dance in front of the wing commander. It’s just not on for our boys to be bathed in glory – unless their name is Albert Ball, at least.” I told them I would write it up and, if I were sent to England, I would post it myself. Otherwise we should have to do get Simpson’s cousin to do the trick. “How many victories has Huntington actually chalked up?” asked Simpson. I responded that his official tally was sixteen and that I had called a number of them into question, which was why the squadron commander wanted me to go away. I also ventured a guess that the squadron commander was beginning to have his own doubts about Huntington. “Now, Reggie – here is the gist of the second letter. This one is from Apollonia to Huntington himself. I’ll make sure this gets posted after the Evening News has run its article. Ready? Here goes. My dearest Samuel, I am terribly frightened that I have got you in serious trouble. I recently shared a couple of pages from one of your letters with a journalistic acquaintance. All I wanted to do was show how our brave aviators were toiling unrecognised whilst the enemy wins glory in the press through their exalted Richthofen. Two men visited me today, a naval intelligence officer and a man from the Air Board. They were asking questions about you and demanded to see all your letters. It was ever so embarrassing! They poured over your most tender thoughts and heartfelt confessions with their grubby paws and questioned me for two hours about what I knew of your station, aircraft and equipment, and your opinions on the war and the war leadership. Oh Samuel, what have I done? I fear that I have jeopardised your career by wishing so much to make you a hero as you so deserve. They made such awful threats. I cannot face you again. With heavy heart, I leave you forever… Apollonia.” Your “The man will be beside himself,” said Simpson. I took great care preparing the two letters the following day and hid them away in my valise. That evening, 4 May, I shot down a lone DFW near Bethune. This brought my tally to 14 enemy machines. On 6 May, I led a flight over the lines just north of Arras. We were jumped by a large formation of Albatros scouts – every one of which was covered at least partially red. These were the Baron’s boys. For the first few minutes it took all my skill and attention simply to avoid their fire and evade collision. Then, as the fight spread out across the sky, I found myself turning and twisting with a red and green Hun. The enemy pilot was highly skilled. Although my machine was in theory the more manoeuvrable, I soon lost the advantage of height to this fellow. Spotting a nearby cloud, I decided it was time to get away and did a half roll and dived beneath him. There was a splintering sound and the lateral control became mushy. The starboard main strut had begun to split. If it came apart my machine would break up in the air. No longer able to throw the Triplane about, I maintained a shallow dive toward the cloud and prayed. Tracer streams passed overhead and one or two rounds hit my machine. Then, mercifully, the wispy arms of the cloud surrounded me. I regained our lines and put the Tripe down in the first flat field I found. It was nearly midnight when I returned to Auchel. Time for one drink before bed. The squadron commander entered the wardroom behind me. He ordered two whiskies and motioned for me to join him by the fire. The words he used were kindly, but he made it clear that I would be leaving the squadron. He could not continue with Huntington and me in conflict. He also made a point of saying that he did not expect me to apologise to Huntington and that he understood my point of view – not that he necessarily agreed with it, just that he had heard and understood it. That was as good as it was going to get. He told me I would not be flying in the morning and would have a week’s leave. I was to be appointed as a flight commander with the Dover Defence Flight. This was a small formation of about eight aircraft, part of the defence of coastal Britain against enemy Zeppelins and bombing raids. We spoke at some length about the squadron, the various personalities who had come and gone, the early days at Vert Galant, and then some technical matters. We shook hands and left as good colleagues should. May 1917 – Leave I arrived in Dover on 7 May 1917 after a rough passage in a destroyer, the name of which has quite escaped me. I reported to the aerodrome on Gunston Road, just north of the town and castle, there to discover (to my complete surprise) that there was no commanding officer to whom I should report at that location. The Wing Commander was in Dover and it appeared that I was the commander of all I surveyed at the aerodrome – a “squadron minus”, consisting of five Sopwith Pups and a pair of ancient Bristol scouts. I stayed there only an hour or two to chat with the pilots and meet for a while longer with Flight Lieutenant Munro, a diminutive Cumbrian who was in temporary command of the flight. None of the chaps other than Munro had experience in France, and Munro’s experience before being sent for flying training and drafted to the Royal Navy Aeroplane Station at Dover was as an observer with Naval Four. The Wing Commander was away at a conference and I reported to his Number One. There I learned that I had leave until 16 May. The first thought was to do what we all did – make a straight line for London, get blindingly drunk, and then visit dance halls and theatres. On reflection, however, that did not truly interest me. I knew no one in London and was thoroughly exhausted. My months in France had not affected me the way it had so many of my colleagues. I had not suffered from nightmares, the shakes, irritability, and growing dread of war flying, but now that I was in Britain I felt an overwhelming sense of fatigue and loneliness. I went to the train station and found a locker for my possessions, then bought a haversack, into which I stuffed some work trousers, drawers and singlets, and a work shirt. I found a shop where I could buy a water bottle with a cork stopper, breeks, long woollen stockings, and a simple jacket. Having nowhere to change, I booked myself into a small and cheap seaside hotel to spend the night. After dinner, I bought a copy of the Evening News and addressed an envelope to its editor in the hand of Apollonia Willing. The postmark would not say Torquay. With luck, the envelope would be thrown into a wastepaper basket before being given to the editor. I slipped the letter I had prepared into the envelope and left it with the front desk for the evening post. In the morning I took to the road. A cool drizzle soon gave way to bright sunshine and clear skies as I walked westward along the coast. I was in Folkestone for lunch, after which I left the main roads and wondered through the north part of town until I found a good walking path into the countryside. I found a pub with simple lodgings near Brabourne and made an early night of it, dining on steak and kidney pudding, chips, and good (for wartime) ale. The publican discovered that I was a Canadian flyer and from that point would not accept my money. Needless to say, I was rather late getting back on the trail in the morning. Over the next several days I wandered northwest through the verdant hills and lush valleys of the North Downs until I came to Wye. From there I turned north-east, arriving a couple of days later at Canterbury. There I spent two nights and enjoyed my days exploring the town and its famous cathedral. The papers were reporting that Albert Ball was missing. It was good to be in England. Everyone runs out of luck eventually. Finally, I took the train back into Dover to retrieve my possessions at the station. I booked myself into the Grand Hotel with the room overlooking the Granville Gardens. There I enjoyed a hot bath and had my uniforms laundered and properly pressed. I found a good military tailor in town who furnished my cuffs with the star designating a flight commander. Thus equipped, I went on 15 May to take over my first command. 16 May - 18 June The first few days at RNAS Dover were spent getting to know our people. The pilots are mostly inexperienced. All are British except for Sub-Lieutenant Henderson, a Canadian from Toronto. I am capably assisted by Chief Petty Officer Blackwell, who oversees general discipline and is also in charge of the aircraft mechanics. I lack a records officer but have a petty officer paywriter fulfilling that role. One of the first things I shall have to do is sort out priorities with the Chief. The flight exhibits a degree of spit and polish that would be most unusual in France. I should like to see that relaxed very slightly. On the other hand, not enough attention is paid to the technical side of our operation. I want the mechanics to duplicate all control wires on our machines and I want the pilots to begin paying personal attention to the zeroing of their machine guns and to their ammunition. I have flown with the men every day, striving to improve their formation work. The only exception was on 19 May, when I flew a Sopwith Pup to Gosport, near Portsmouth and not too distant from Torquay. There I posted Apollonia’s farewell letter to Huntington. I must be an evil man, for I did not feel an ounce of guilt. On 20 May, we were joyfully astounded to learn that we had been allocated two of the latest fighting machines by Sopwith. These machines have been nicknamed the “Camel” because of the hump-like protuberance over the breeches of their twin synchronised Vickers guns. I have claimed one and Munro the other. Frankly, it frightens me to consider giving these things to some of our pilots. The Camels are unstable creatures requiring full rudder on takeoff to counter the powerful gyroscopic effect of the 130 horsepower Clerget rotary engines. In a left turn, the nose wants to point up at the heavens and a stall is easy to induce. In a right turn, the nose wants to snap under the rest of the machine and a spin is difficult to avoid. And if you enter into a spin, it is the very devil to get out of it before the ground hits you in the face. Munro and I spent the first two days gingerly learning to coax this wild beast to follow our commands. For all its frightening habits, the machine promises to be the nimblest thing in the air if you can tame it. On 25 May we received a call warning of approaching enemy aircraft and we patrolled for more than an hour from Dover up to Manston. Unfortunately, the Huns failed to show up for the party. Three more weeks of uneventful patrols followed. Finally, on 13 June 1917, we were dispatched to intercept an expected raid by Gothas, the giant two-engined bombing machines the Germans have unleashed on England. Instead of climbing to altitude near our aerodrome as we usually did, I told the boys to meet up over Margate, as this was where the enemy was expected to make landfall. In our Camels, Munro and I climbed away from the others. We passed west of Ramsgate at 10,000 feet and saw Archie bursts in the distance to the north-east. Climbing hard, we were astounded at the view. Wave upon wave of giant aircraft were approaching the coast east of Margate. I estimated at least fifteen or twenty Gothas. Looking behind, I realised we had left our pups and Bristols far behind. I fired a red flare and signalled to Munro to attack the enemy directly. When we were still almost a mile from contact, the leading Gothas began releasing their bombs and turning away eastward. The trailing Huns dropped their bombs over water and turned back. I picked the machine I was most likely to intercept and climbed for it. My selected Gotha had been one of the trailing machines but now was near the front of the pack running home. Unfortunately, there were other Hun machines behind and above me, but there was no avoiding them. I would have to take my chances. Thanks to the powerful Clerget I began to close on my Gotha and pulled out of range of the enemy bombers behind me. When I was about 300 or 400 yards away, its gunner opened fire. We had been puzzling for a couple of weeks about whether the Gotha had a machine gun that could fire downwards. My impression was that it certainly did. Although I was nicely tucked under the Hun’s tail, his rounds were snapping past my head. Then another Gotha off to my port side began to fire. I held fire until I was 200 yards away. By this time several rounds smacked into my Camel. I fired a long burst without any visible effect – I was clearly too nervous to shoot well. I began a second burst when suddenly the forward port cabane strut splintered and I felt a whiplash across my face. I pulled away involuntarily and, true to its nature, the Camel entered a spin. By the time I recovered my machine had dropped several thousand feet and the Huns were well out to sea. I had blood on my flying coat and my goggles had disappeared. I throttled back and began a gentle glide homeward. On landing I was driven to the Royal Victoria Hospital in Folkestone where a great deal of Camel was removed from my temple, cheek, and jaw. The injuries were neither painful or debilitating, despite which I am required to remain in a convalescent hospital for a week to ensure that the minor wounds do not become septic. Munro has visited twice and kept me up to date with news of the flight. -

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion

Lederhosen, The correct date for the campaign should be this date in 1917 – at the time I am writing this it would be 18 August 1917. Because of personal circumstances, I have been unable to keep up with the calendar. My pilot will soon be transferred to Home Establishment where he will fly less often, thus allowing me to catch up. Raine -

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion

Journal of FLt Douglas Bell-Gordon, RNAS Part 19 3 May 1917. Auchel, France. "The DFW banked hard and dived under us." Like so many mornings since I arrived in France, this morning began before sunrise when Macklin, our steward, shook me gently by the shoulder and whispered, “Just after three-thirty, sir. Promises to be a fine morning.” He left me with an enamel mug of strong, steaming, sweet black tea and three lovely ginger biscuits. Crundall was on leave and I was to lead the flight this morning, a close offensive patrol along the German lines from Arras up to La Bassée. I met the others of the patrol by the sheds and quickly went over our routine. By the time the eastern horizon paled from deep violet to dark blue we were turning into the wind and bouncing over the stubbled field. Spring was finally making its presence felt. Scarcely a cloud in the sky and the chill failed to penetrate the layers of leather, fur, wool, and silk until we passed 5000 feet. Formed up, we turned southeast towards Arras and continued to climb toward 12,000 feet. Archie welcomed us to Hunland. We turned north over Monchy and began our patrol. Such a glorious day – virtually no chance of being surprised. Occasional clusters of Huns appeared off to the east, but none dared approach us. Over La Bassée canal we turned back south. Archie fell into a predictable rhythm: scattered over Lens, then thinning out, then slightly heavier at the balloon line near Oppy, and finally bloody annoying over Monchy. Then around to the north and do it all again. And again. Ninety minutes in. McDonald came up alongside and waggled his wings, pointing to the northwest. I turned in that direction and began to climb toward two specks about two miles off and slightly above. As we approached them that it became clear that we were creeping up on a pair of DFW two-seaters. There were six of us struggling to keep safely under their tails. When we were still 500 yards behind and slightly below, the right-hand Hun must have spotted our approach for he peeled away and dived east. I signalled for the others to chase him and continued after the remaining two-seater. McDonald stayed with me. This was an experienced Hunnish crew. The observer held fire until we were only 150 yards away. I began to fire in the same instant that he did, and we both scored hits. As I broke away, McDonald had a go. The DFW banked hard and dived under us. McDonald and I took it in turn to fire at him, each trying to approach from an opposite side so that the Hun observer would have to swing his gun about before firing back. After several such exchanges, McDonald must have turned the wrong way for I lost sight of him. I caught the Hun in another steep bank and raked his machine from tip to tail from directly above. It took several seconds to find him after that pass. We were down to less than 1000 feet. There he was! The DFW, grey-green with a camouflaged upper wing, was in a shallow dive and trailing a stream of vapour or white smoke. Now McDonald came screaming down at him from above but overshot the Hun, whose observer gallantly kept up his fight. I dived onto the tail of the HA and fired one last burst. The machine continued down and I thought for a moment it would land safely in a broad green field, but its undercarriage caught a treetop and the aircraft smashed heavily into the ground and disappeared in a cloud of earth and flame. We regrouped and soon afterward headed home. The other HA had got away. I claimed the one that was downed and McDonald vouched for its destruction. Once D’Albiac took our reports, he asked me to complete a written account of the claim. While I was doing this, the squadron commander entered the office. Squadron Commander Bromet directed the Records Officer to leave us alone for a few minutes. Once D’Albiac had closed the door behind him, the boss sat stiffly in his chair and eyed me carefully. “What I have to say is, for the moment, between us. It is also a painful topic to approach,” he said. I looked at him a little sideways. What horrid news had arrived? Were my parents all right? The squadron commander continued. “A rather serious allegation has been made about you by a flight commander. Do you know what I’m talking about?” “No sir. I have no idea at all.” Bromet sighed and winced. “Yesterday you led a flight of five Triplanes escorting three RE8s from 52 Squadron on a diversionary bomb run near Vitry. Flight Commander Huntington led a second flight of six machines to provide you with support. I am informed that Huntington’s flight was engaged by hostile aeroplanes and destroyed three of them. At the same time, you led your flight away from the enemy and failed to support Huntington. As a result, the enemy nearly succeeded in destroying Mr Arnold’s machine and Huntington himself was left to face several Huns alone. What is your response, Douglas?” I could feel my breath shortening and my heart pounding beneath my tunic. Rage boiled up. I took three or four deep and deliberate breaths before responding. “Let me begin by stating that I am doing my damnedest to be measured and objective in what I am about to say. So I will begin by saying this. Flight Commander Huntington has absolutely no basis to believe that what he has told you is the truth. I can presume, therefore, that his intent is malicious. He is lying about me. He knows he is lying about me. And I therefore hold him in complete contempt.” “Mr Bell-Gordon…” I held up a hand and cut the boss off in mid-breath. “Let me recount that patrol. First, we took off around ten minutes after four in the afternoon. My flight formed up in three or four minutes and we circled over Bruay as we climbed to seven thousand feet. I looked about for Huntington’s flight but they were nowhere to be seen. After waiting there several minutes, I headed north north-east towards our rendezvous point south of La Gorgue. We spotted the three Harry Tates from two miles away and joined them quickly. From that point, we kept station about a thousand feet above them as they climbed south-west toward the lines at Vimy. We crossed into Hunland at eleven thousand feet and followed the two-seaters as they approached Vitry. This was a bit after four-thirty. Soon after we crossed the lines I noticed Archie bursts off to the north and the little west – probably a bit west of Lens. It was not possible to make out the aircraft, but I assumed that Huntington’s flight was trailing well behind us and at a distance of four or five miles.” Squadron Commander Bromet was scratching notes on a pad of paper. I waited until he stopped writing and continued. “I angled off to the south so that I could watch the RE8s more easily. At one point I observed five or six scouts several miles off to the north-east. We stayed with our wards and these Huns – I’m certain they were Huns – flew north out of sight. Near Vitry, the 52 Squadron machines began bombing their targets as we circled above them. After about five more minutes, I made out Huntington’s flight of six Triplanes. They passed us to the north and continued several miles to the east. At the closest point we were only a mile apart. Strangely, they were descending.” “The 52 Squadron machines took about ten minutes to finish their work and another five or ten minutes to reform afterward. During this time I saw Archie several miles to the east and presumed that the Huns had found Huntington but I could not see any machines at that distance. The RE8s now began heading home and we zigzagged in station behind them. The entire time I kept looking back for Huntington’s flight. At no time was he in a position to support us had we come under attack. As our two-seaters crossed back over the front, I led my flight in a long turn back to the east. I had spotted a formation of several Hun scouts heading southeast toward where I thought Huntington must be. I left them and turned south after a couple of minutes so as to continue to watch for Huntington while maintaining contact with the two-seaters. Then I noticed two Triplanes heading west around five or six thousand feet. I then made out several aeroplanes milling about just north of Vitry. I could not positively identify every machine, but I saw that at least three out of five were Triplanes, still well to the east. Seconds later I saw that those remaining Triplanes were heading west and were not being followed. By this time, the 52 Squadron machines were well to our west and we raced after them at full throttle, catching up near Arras. Shortly after that, I signalled for my flight to return to base.” “Is that all?” the boss asked. “No sir. As we descended on our way back to Auchel, I caught up with and passed close to Mr Arnold’s machine. He had clearly been the first of Huntington’s flight to head home, having passed beneath my flight about the time that I first saw Huntington’s machines mixed up with one or two Huns. At no time did Mr Huntington’s flight require our assistance. And at no time would matters have justified my flight abandoning the two-seaters. Finally, sir, may I ask whether Mr Huntington has explained to you why he wandered off in the direction of Douai and descended to five thousand feet instead of covering my flight from twelve thousand feet in accordance with his instructions? Or is that question answered by the fact that he has claimed three Huns downed after his flight headed home and there were no witnesses to his claims?” “That comment is completely out of line,” said the squadron commander quietly. “Merely a question, sir. I apologise if I insinuated that Mr Huntington is a liar. It was not intended as a mere insinuation.” “We’re done here.” With those words, Squadron Commander Bromet snapped the cap onto his pen and placed it on his desk. I found Simpson and Reggie Soar in the wardroom. “Emergency meeting of the correspondence club at Madame Girouard’s place after dinner. I have a plan and we need to see it done right away.” -

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion

It has been far too long since my last post. Between my own health issue and my wife suffering from a nasty fall on the stairs, real life has precluded much campaign flying. I am well behind but will try to catch up. At least I don't have to worry about being out of sync with other contributors. With luck others can rejoin the campaign in time to take advantage of the two promised updates/expansions from OBD. These sound tremendously exciting. Journal of FLt Douglas Bell-Gordon, RNAS Part 18 30 April 1917. Auchel, France. "A small but intense puddle of flame appeared in front of the pilot." The battles around Vimy continued through until 12 April, but we were grounded for three days by bad weather – including sleet and late snowstorms. On 11 April, I led a flight of five machines over the lines near Arras and spotted a Hun two-seater. It dived away after I expended more than 200 rounds, but we could not tell if it crashed. Meanwhile Huntington continued with his claims. According to routine orders, he is to be awarded a bar to his Distinguished Service Cross. On 12 April, I was with a flight that encountered four Albatros scouts over Vimy. Because of the poor weather that day we very nearly collided before seeing each other. The fight was chaotic for the first few minutes – machines flashed past leaving time only for the briefest burst before one had to zoom or jink violently to avoid enemy fire. Then, as quickly as it had started, the “dog-fight” (as they are coming to be called) broke up. I spotted and dived upon a lone HA, a black Albatros with a white band around its fuselage. Closing to 50 yards, I fired a long burst and saw flames erupt from the engine. It was a horrible sight and I climbed away with only the briefest glimpse to confirm that the Hun was falling vertically streaming flame and thick black smoke. This one was confirmed for my eleventh victory. We flew once or twice every day in the week that followed and had several inconclusive scraps. On the ground, however, events were more interesting. Simpson, Reggie Soar, and I continued our correspondence with Huntington under the pen name of “Apollonia Willing.” And Huntington for his part gave into his baser instincts and fell head over heels for the young lady that we had invented. Every few nights, the three of us conspirators retired to Madame Girouard’s estaminet in Auchel, ordered a bottle or two of plonk, and wrote another letter to our boastful colleague. Things began to turn steamy when Apollonia regaled Huntington with the theme of a novel by Elinor Glyn that she had just read – one involving the heroine playing horizontal rugby on a tiger skin with a dashing young nobleman. Huntington rose to the bait. His return letter a day later was intercepted by Simpson. In it, Huntington described a lengthy and breathtaking conflict with Baron von Richthofen, the master Hun pilot who had made a considerable name for himself of late. He claimed to have come within a hair’s breadth of downing von Richthofen. According to the letter, the Baron pretended to surrender before cravenly diving away home when Huntington drew alongside him to salute his skill. “I am quite sure that I should have earned a Victoria Cross had the dastardly fellow not done me such a caddish turn,” he wrote. He then professed his deep love and shallow lust for Apollonia. In her response the following week, Apollonia fantasised about their future racy encounters when Huntington next came to England on leave. The jape was getting somewhat beyond our control. Huntington sent a package of lace underthings to Apollonia, which Simpson discovered and intercepted moments before it was picked up by the outgoing post despatch rider. Huntington had spent a fortune on this gift and we felt somewhat guilty that the woman he’d lavished his pay on was a figment of our evil imaginations. Reggie, however, secreted the items away and confided that he knew a place in Amiens where such things would be appreciated. We headed back to the estaminet in Auchel on the night of 19 April and, persuaded by a third bottle of wine, created an erotic masterpiece of a letter from Apollonia to Huntington, one that would certainly render him mad. Huntington continued to file claims, several of which were completely genuine but more of which were dubious. He was indeed a good scout pilot and a fine shot, but at least four claims were unwitnessed yet confirmed by Wing. One of our colleagues – I shan’t say which – voiced his scepticism in the wardroom and brought the wrath of Squadron Commander Bromet down on his head. Yet we were all of the opinion that the skipper was himself beginning to question Huntington. Still, Huntington now had twenty victories to his name and was due for leave. Indeed, if it were not for the current offensive and the pressure we were coming under from the number of superior German machines over the lines, he would likely have already headed back to England. Simpson, Soar, and I began to discuss ways to bring the whole charade to an end. On 25 April, I led a patrol of five Triplanes on a defensive patrol to the north. There were reports of several enemy observation machines on our side of the lines. After an hour of fruitless searching as far up as Armentieres, I turned south for one more sweep. A couple of miles ahead and to starboard, several light grey puffs of Archie betrayed the presence of a lone Hun. I signalled to the others that the chase was on. They soon left me behind as my machine was not giving full revs. This would not be my day, it seemed. But then it all changed. Crundall and Rex Arnold were well above and banging away at a DFW. The Hun turned on its side and fell into a vertical spin. I watched as it dropped past me and passed through a thin cloud. For whatever reason, I became suspect and dived after the two-seater. Sure enough, the Hun pulled out of the spin a couple of thousand feet above the ground. The observer was angrily pounding on the shoulders of the pilot. Poor fellow had been holding on for dear life all the way down. But this was no time for sympathy and I began firing from 150 yards. A small but intense puddle of flame appeared in front of the pilot. I watched in horror as a plume of black smoke poured from the stricken machine, which rolled slowly onto its back and fell in flames directly downward. The observer, just moments before angry after narrowly avoiding death, now fell free of the DFW and momentarily hung spreadeagled until his leather coat was torn away by the wind and he tumbled, disappearing into the backdrop of fields below. The Hun was confirmed as my twelfth. After the intensity of the past few weeks, April ended with a succession of uneventful patrols. It was announced this evening that leaves will be reinstated shortly. Huntington is off to Dunkirk tomorrow to receive his second DSC from the Admiral. He complained at dinner that he should really have received an invitation to an investiture at the Palace. “I really had planned on taking Apollonia along to meet the King,” he said. “Poor girl will have to make do with meeting my parents.” “We’ll need to meet for our correspondence club soon,” Simpson whispered to me over coffee and brandy. “This thing needs to be put away.” -

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion

Von S – Thank you for your kind words. It's wonderful to see you dropping in on the campaign. I am well behind and trying to catch up. My PC that I use for WOFF used to be at the apartment in town that was part of my company office. I would stay in town during the week when I had early morning appointments as we live in the country about an hour away. But because of my condition (ALS/MND), it's now easier for me to work from home. So I have set up an office in our guest apartment attached to the house. The only problem is that I have a very large window at my back and the light interferes with my track IR until sunset. There were no blinds on that window as we are surrounded by woods and wonderfully private. Now I've ordered blinds and am waiting to have them installed. I have about a month of catching up to do. Anyway, here is another instalment that brings Bell-Gordon's story to within a week of where my actual flying has taken him. More to follow later, I hope… Journal of FLt Douglas Bell-Gordon, RNAS Part 17 10 April 1917. Auchel, France. "An Albatros appeared just ahead and below. The fuselage and tail of the machine was entirely washed over with red paint." So much to write about. April began with rain and sleet. On the first day of the month, I went into the town with Crundall. We have arranged with the mining company for access to their well-appointed bathhouse, so we soaked ourselves for an hour and then retired to a café for omelettes and chips. I’m not sure what magic these French women perform when they crack an egg, but the omelettes here are unforgettable. The one that morning had onions and scraps of pork mixed in with the egg. We had just returned and settled into the wardroom for a rainy afternoon when the post finally arrived. The despatch rider left everything in the squadron office. Fortunately, Simpson was working on the journal there and immediately volunteered to sort the letters – one pile for the chiefs and petty officers, another for the lower deck, and a third for the wardroom. With his body between D’Albiac and the counter he was able to slip from his pocket a scented yellow envelope and place it in the middle of the wardroom pile. Later in the wardroom, Rob Little spread the post on the bar and called out the names of the addressees. When he said, “Huntington”, Huntington sat bolt upright in his armchair by the fire. Rob was examining the envelope. “A bit of a sweet pong on this one, by God! I didn’t think your Eliza would wear a scent quite so…forthcoming.” Huntington rushed to the bar. He snatched the envelope and examined it. “Come on, lad,” said Reggie Soar. “Read it aloud.” Huntington tore open the envelope. He noticed and began to remove the photograph of our creation, Miss Apollonia Willing. But after a momentary glance he tucked it back inside. He then unbuttoned his tunic and slipped the letter into an inside pocket. Reggie protested loudly and others took up the cry. Huntington protested. “It’s from one of those trollops that Galbraith persuaded to write you lot. I shall likely consign it to the stove. Regardless, a gentleman does not share letters from the opposite sex as wardroom entertainment.” He got up and headed directly to the flight commanders’ cabin. The following morning, 2 April, dawned clear and frosty. The original plan was to conduct a line patrol from Lens down to Arras. It was becoming clear to all of us that the impending push was directed at the high ground near Vimy, west and south of Lens. Then, just before seven in the morning, Huntington informed us that enemy two-seaters were approaching the lines near Lens and we were to drive them off. Our machines were rolled from their sheds and run up. We dressed quickly. I could not find my scarf and tied my pyjama trousers around my neck to keep the wind from penetrating the flying coat. Huntington made a point of saying I look like a bloody gypsy. We had only a minute to prepare. Huntington would lead and my machine would carry the single streamer of the flight second in command. He wanted me above and behind the main formation. We refer to this as the “sacrificial lamb” position. Then we took off. After gaining height over Houdain, we headed for the lines at 6000 feet and climbing. A few desultory Archie bursts drew our attention to a pair of two-seaters heading south from La Bassée. Huntington went straight for them without trying to get the sun at our backs. The Huns spotted us when we were still two miles off and put their noses down and ran for home. We followed them as far as the other side of Lens but gave up the chase when they drew us too low and the Hun Archie began paying us their compliments. As we climbed back westward, Hervey waggled his wings and surged forward to get Huntington’s attention. The formation turned to port and inclined towards the south. There they were! About six or seven dark specks coming directly out of the sun. We continue to climb towards them and within seconds the sky filled with tracer streams and aircraft. The Huns were Albatros vee-strutters, the latest type. More troubling was that they were all somewhat red. We had learned that this was the colour scheme of Jasta 11, a club of particularly keen Hun pilots led by a baron who is a bit of a star turn. I climbed sharply and banked hard to starboard, looking about. Two Huns were below and circling with a pair of Tripes. Two are three more were off to my port side. Then streamers of smoke flashed past my head. There was a Hun in my blind spot. This time I rolled sharply left and then zoomed. An Albatros appeared just ahead and below. The fuselage and tail of the machine was entirely washed over with red paint. Even the black crosses were covered, although I could make out the faint outline of a cross on the tail. There was time for a quick burst. The Vickers popped away for a couple of seconds and rounds hit the fuselage of the Hun machine. Then the all-red Hun did an S-turn below me. For several seconds he seemed gone. Then once more rounds were snapping past my head. I pulled away in a climbing turn. By the time I turned about the sky was empty and the red Hun was gone. The next few days were busy but uneventful. The gunfire along our sector of the front smashed at the enemy lines around Vimy, an unceasing and stomach-turning assault of noise. Above Vimy, our machines were everywhere. Our task was to patrol just over the enemy lines. The Germans dared not approach. We flew, we searched the sky, we froze, and we went home. Yesterday, 9 April, the storm broke. Our own Canadian Corps, four divisions strong and with British divisions on either flank, swarmed forward over the churned-up mud and wire of Vimy Ridge. At the south end of the ridge, our boys advanced more than 4000 yards and seized their objectives around Thélus. The central spine of the ridge fell by midday and from high above we could see the Huns staggering eastward, away from the fight. Only at the north end of the ridge did the enemy line hold. That day we patrolled three times and twice ran into desperate attacks by Albatros scouts. On my third patrol we met our old friends from Jasta 11 once again. They were good, these Huns, and I threw my poor Tripe all about the sky while avoiding their fire. Suddenly I heard a sharp crack and knew that something was seriously wrong with my aeroplane. The starboard upper wing showed a concerning amount of flexion and the ailerons scarcely responded. I throttled back and headed west, praying all the while that the wing would remain part of the machine until I could get down. Luckily, none of the Albatri decided to follow. I found a field just behind our lines and settled down into it. At least, that was the plan. But just before touching down the ailerons decided not to respond at all, and the port wings dropped and hit the half-frozen earth. My Tripe cartwheeled across the field and, somewhere before it settled into a ditch and crumpled itself into a ball, I was ejected and landed on an embankment. I have never been so winded or bruised. Nothing, however, is broken. Squadron Commander Bromet has given me a day off. Meanwhile, Huntington claimed two Huns from the scrap. One was almost certainly Crundall’s. I had seen Crundall chasing it and shortly thereafter saw the German – yellow with a red nose – spinning earthward. Huntington asserted that the Hun levelled out and he dived on its tail and finished the fellow off. No one wants to say anything but there are several of us looking sideways at Huntington. After dinner, Simpson got hold of Reggie and me and insisted on walking to town so he could buy us a bottle of wine. He would say nothing more until we were safely ensconced in Madame Girouard’s estaminet in Auchel. There he produced his secret – a letter in Huntington’s hand addressed to Miss Apollonia Willing in Torquay. He had successfully intercepted the outgoing mail. The wine was poured and he read it aloud. “Dear Apollonia, “I pray that I am not too forward in addressing you by your Christian name (is Apollonia truly a Christian name?) when we scarcely know one another. Yet I have read your letter so many times since it arrived yesterday and feel that we are destined to become good friends. Lord knows that I need some good friends. You should see the lot that I am saddled with here. They are an uncouth mob. More than half of them are Canadians and Australians and are still walking about with their mouths open at the wonders of a civilised world away from the prairie or the outback. Still others are barely above the most common of working men. They are unschooled and unsophisticated with few exceptions. One can simply not have an intelligent conversation. And as their commander, one must bear responsibility for their sad lives. I think only that I have perhaps the opportunity to leave them better persons than they were when they came to the Navy. “You said that you were told that I had enjoyed some success here. One shrinks from revelling in success when success means killing another human being. The beastly Huns, I tell myself, are scarcely human. It is a story that eases the soul. I have lost count of how many Huns I have bagged, but the squadron commander tells me it is somewhat more than twenty. Perhaps you have heard of Albert Ball. He is a pilot of the Royal Flying Corps and has downed thirty Huns. But Ball is back in England, so perhaps I have a chance to catch him or, who knows? “Thank you for sending me your photograph. I shall try to reciprocate if I can find an officer here able to use a camera. You asked me if I was fond of a girl. Until this week, I devoted all my energy to fighting our enemy and have never thought of pursuing any woman. Now I must confess, Apollonia, that I keep your picture hidden near my bedside and wonder nightly whether one day we might meet. Do not spare a thought that you could be a distraction for me in the air. My devotion to my duty is unshakeable. But put my feet on the ground? Ah, now I find my thoughts turning to you and to the sentiments you shared with me. “Do you like poetry? I am very fond of Shelley and Yeats. Please share with me all your likes and dislikes. For my part, I will dedicate all my efforts to you. “Your devoted airmen, “Samuel Huntington.” Simpson put the letter down on the table. “Well, chaps, that’s the end of Eliza it seems.” We were laughing hysterically, although I suspect we all felt a slight tingling of guilt. -

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion

It's been a while. I have moved my main PC back home from the apartment in town where I stayed many nights during the week while working. I'm gradually disconnecting from that whole "work for a living" thing. The previous post is the first of several instalments it will take me to catch up. And the following are the month end statistics for Bell-Gordon. Flight Lieutenant Douglas Bell-Gordon 8 Squadron Royal Naval Air Service Auchel, France Sopwith Triplane 82 missions 56.43 hours 26 claims 10 victories -

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion

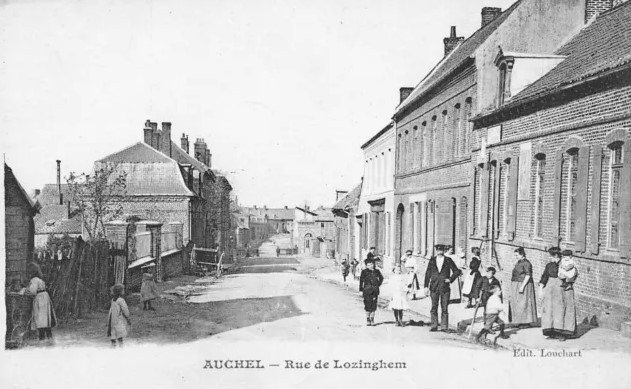

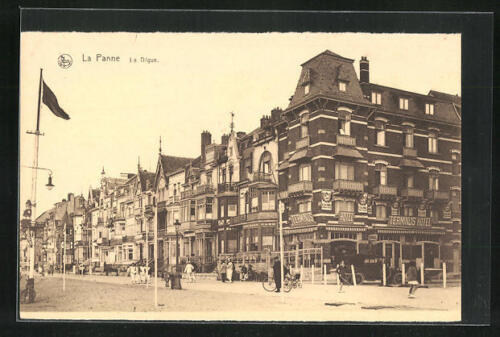

Journal of FLt Douglas Bell-Gordon, RNAS Part 16 24 March 1917. Furnes, Belgium. We’ve had a week of grey skies and cold drizzle, relieved only by periods of freezing rain and wet snow. Patrols have been uneventful. Simpson has been made a flight commander and so has Huntington. The latter claimed a Roland yesterday and it was marked up as his eleventh. The talk in the wardroom centres on the many young ladies of London who have taken up correspondence with the chaps ever since Galbraith was drafted back to a seaplane squadron that in England a few months ago. Galbraith was a fellow Canadian whose sister was a Red Cross nurse at a hospital in London and who had undertaken to have her colleagues write to lonely aviators. Every few days Reggie Soar received a letter from Grace. Roderick McDonald is corresponding with Dolly. Crundall has been sent letters from Margaret. And I have begun a mild correspondence with a girl named Alice. So this afternoon, Reggie was enjoying a glass of brandy and a pipe whilst reading to us a poem written by his Grace – a poem about, of all things, flying! Raised up from English soil and blessed with English sun, He rises from the earth to stalk the frightful Hun, Girded not with armour but canvas wings and wires He jousts with England’s foes above France’s lofty spires! Hoots of laughter. Jenners-Parson grabbed the letter from Reggie’s hand and set it alight. Reggie tried to get it back and in the process dropped it onto one of the overstuffed armchairs. Disaster was narrowly averted by throwing the flaming chair outside into the rain just in time to splash mud over Prince Alexander of Teck, who was arriving with Squadron Commander Bromet for tea! Huntington sat apart from us all this time and, once tea was over and the higher-ups had left us alone, he came over to give us a dressing-down. We were bloody fools and what we had done was dangerous, he said. Furthermore, we were unkind to Reggie who was lucky enough to have someone who cared for him enough to write letters. As a flight commander, he would not put up with such behaviour. “You should be thoroughly ashamed of yourselves,” he told us, “and especially you as a flight commander, Simpson.” And then he added, “Galbraith should have known better than to start this nonsense.” “Has a girl written you, Huntington?” It was Simpson who asked. “You know full well that I have my Eliza,” Huntington replied. “No need of anyone else.” “Strange. I don’t recall you ever getting letters from Eliza.” Huntington’s face pinched. “In the first place, Simpson, it’s none of your bloody business. Eliza sends her post along with letters from my parents. She is very close with the family. Should be part of it one day, I suppose.” I couldn’t help joining in. “Are you sure this Eliza is not a cousin, or perhaps a hideous sister you’ve forgotten about?” “You disgust me, Douglas, you really do. Of course, one should probably expect that sort of thinking from a colonial homesteader, I suppose.” As luck would have it, I was seated next to Roddy McDonald. Roddy hailed from Antigonish, Nova Scotia, where his family had farmed a homestead for several generations since being evicted from the Highlands to make room for deer. “Mixed up as usual, Huntington,” I said. “It’s Roddy here who is the colonial homesteader. I’m the colonial hockey player and Navy brat. Then there’s Simpson. He’s the colonial sheep shagger from down under. And Hervey, he’s the colonial peas souper from Québec. Bob Little over there is another colonial sheep botherer. Hell, as if being Australian is not bad enough, his old man comes from Canada. Then of course there’s Grange over in the corner. He’s a Yank, so he only wishes he were a colonial. You’re outnumbered by us colonials, old boy.” Huntington left in a huff. That evening I received permission from Squadron Commander Bromet to take dinner in La Panne along with Simpson and Reggie Soar. We’d found a comfortable little estaminet on a side street, well away from the more frequented establishments. The woman who ran the place made a genuinely decent cup of tea, and once we were settled I cleared the centre of our table and laid out my package of tricks. “My God, a Dorothy bag!” Reggie exclaimed. “Haven’t seen one of those since the Dardanelles.” “What did you call it?” I asked. Reggie explained that “Dorothy” bags were issued on hospital ships so that the wounded men could store their personal possessions. Mine apparently was a very fine version of what he had seen. “I got it from a nurse. Interestingly, and she was called Dorothy, too.” I gave Simpson a wink. The bag was the package I’d received from Simpson’s cousin Dorothy and her friend Patricia when I had been invited for dinner with Simpson’s parents in London a couple of weeks before. I reached inside and withdrew a small photograph of a young woman. She was idyllic – languorous eyes, fair hair falling in ringlets, noble cheekbones and a fine, strong nose above perfect lips and delicate chin. The lower part of photograph was gauzy. Perhaps she wore a a thin dress low on the shoulders, but it was barely visible and the suggestion of nakedness was tantalising. “Meet Apollonia Willing, gentlemen.” “Who is she? She is topping,” said Reggie. “Apollonia is Huntington’s new fancy,” I told him. Simpson was giggling uncontrollably. “Willing? Her name is Willing? Isn’t that a bit transparent?” “It’s Huntington, man. It will be at least a week before the thought crosses his mind.” I withdrew from the Dorothy bag a small pile of yellow stationary embossed with gold floral finishes in the corners. There were at least a dozen envelopes and as many penny stamps. I then explained the plan. The three of us would collaborate in composing letters to Huntington from Apollonia who, of course, was a figment of fantasy. The photograph belonged to the sister of a nurse who worked with Dorothy and Patricia at Saint Thomases’ Hospital in London. She had planned to send it to her boyfriend at the front but thought it too racy. I had been practising a girlish, loopy script that suited the character. Apollonia would be enthralled at the idea of writing to a gallant bird man. Perhaps we could begin innocently enough and gradually make her letters more suggestive and enticing. We would slip Apollonia’s letter into the post at the squadron office shortly before dinner time. The trick would be intercepting any reply from Huntington before our outgoing mailbags were picked up by the dispatch rider in the morning. To this end, Simpson had volunteered to assist the Records Officer, D’Albiac, in maintaining the squadron war journal. He figured he could offer to censor some letters while working in the office, which would give him easy access to the mailbags. Reggie asked how we would make the incoming letters appear to have passed through the post. “Take a look at this,” I said, and pulled the final item from the bag. It was a stamped envelope, addressed in a girlish hand to Flight Lieutenant Samuel Huntington. The one-penny stamp was cancelled with a postmark from Torquay dated 21 March 1917. “It’s perfect,” said Simpson. “How?” “It’s the sixpence ha’penny solution,” I said. “The outer circle is traced in pencil using the ha’penny and the inner circle using the sixpence. From there it’s just a matter of mastering the lettering. I’ve diluted a bottle of black ink with some distilled water and cigarette ash. If you lightly paint it on with a drop of ink smeared on the end of a pencil and nearly dry, you can do a fairly good job. And if you make a small mistake you can always rub it with your hand and make it look like the post office smeared the cancellation.” It was time to order a bottle of wine and begin… “Samuel, my dear boy, we have not yet met but I have already heard so much about you!” It would take several more bottles before we were done. 27 March 1917. Auchel, France. After a period of bad weather the squadron moved again, this time farther south towards Bethune in the Arras region. Our aerodrome is just outside a place called Auchel. It is a rather grimy mining town of squat brick houses and soot-stained buildings that eventually dissipated into the countryside along muddy roads flanked with ancient low farm buildings and middens coming alive with the springtime. Above the town looms two giant mountains of dross called terrils. They have the appearance of great black pyramids standing guard over the countryside. We should have no problem finding our way home here. I’m in the squadron commander’s bad books since I smashed up a perfectly good triplane during my arrival at Auchel. Got away with only a few bruises. 31 March 1917. Auchel, France. We are still awaiting our first postal delivery at the new aerodrome. I am billeted with Simpson in a house at the edge of town. The owners are an elderly couple who speak no English. Whether they speak French is still a mystery as they scarcely talk to each other. I have been over the lines twice since arrival here. By all accounts there are some very keen Huns in the area. Had a scrap yesterday with a formation of Albatri and managed to drive one down. D’Albiac phoned around but no one saw it crash. Today we were sent up to chase off several two seaters in our area. I fired about 200 rounds at long-range at one of them but it got away. April is upon us and with it rumours of a new push. I suspect we are about to get busy. -

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion

Got some catching up to do... Journal of FLt Douglas Bell-Gordon, RNAS Part 15 "Flames immediately began to pour from the engine of the Albatros and I watched it, a black machine with a white band around its fuselage, as it fell in flames directly over the enemy aerodrome" 12 March 1917. Dunkirk. So with the beginning of March I was off to England, boarding HMS Llewellyn in Dunkirk for the quick dash across the Channel. The German Navy had been active during the preceding night and the ship’s complement were clearly on alert. We landed at Dover without incident, and from there the train delivered me to Victoria Station in the heart of London. What a city! My past acquaintance with the place was so brief and so full of preparations for transfer to France that only now did I have a chance to take it all in. I headed out to the street to flag a taxi for Holt & Co to cash a cheque and exchange francs for sterling, then bring me to my hotel on Basil Street. First priority was a long bath and a smoke, all accompanied by a stiff whisky. My hotel is a bit of a walk from everything. Wandered north through Hyde Park and took tea at the marvellous Maison Lyons by Marble Arch. Shopped on Oxford Street and ended my marathon by following Regent Street to the famous Piccadilly Circus. It was growing dark by then and the place wasn’t all it’s made out to be because of the blackout rules. Ran into Pete Maguire from Halifax. He’s over here with the artillery. We enjoyed dinner at the Regent Palace and he suggested that I take in the new show “Maid of the Mountains” at Daly’s. I picked up a ticket on my way home. Took in the Natural History Museum next morning. Met Pete for lunch and then went to see Buckingham Palace. Light dinner at the Trocadero and from there by taxi to Daly’s Theatre by Leicester Square. Played the tourist for several more days – British Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum, and saw “Zig-Zag” with George Robey at the Hippodrome. Joined a small group of Canadian officers for a trip to the Turkish Bath at the Auto Club. Then a most pleasant surprise – the clerk at my hotel informed me of a letter that had been left for me in my absence. It was a dinner invitation from the mother of George Simpson. On the evening of Friday, 9 March, I caught a cab up to Regent’s Park. I’d always understood that Simpson lived in a posh area, but nothing prepared me for the immaculate white, pillared Georgian frontage of Cumberland Terrace. Before I even reached the door of number 29, it was opened by a liveried butler who took my cap, gloves, and walking-out stick (with which I had never before actually walked out). To my surprise, I was met by a Mr Goodman Levy and moments later joined by Simpson’s mother, who introduced herself as Alice. The story tumbled out over sherry. Simpson’s parents were English but had moved to Australia more than thirty years before. Simpson himself was born in Melbourne. They returned to England when Simpson and his brother Rolfe were boys. Simpson’s father taught art but had died six years ago. Goodman Levy was a trusted family friend, also from Australia. Goodman and Simpson’s father were old school chums in Melbourne. Goodman and his brother had a prosperous importing and exporting business and he was something of a wine merchant. When Simpson’s father died, he left money to Goodman Levy, who had promised to take care of Alice. And take care he did! The flat at Cumberland Terrace was immense and Mrs Simpson had two rooms of her own and the run of the place. It was all very proper, of course, and a very comfortable situation for Alice. More visitors arrived – two lovely girls named Dorothy and Patricia. Dorothy is a distant cousin to Simpson. She and Patricia are working as nurses at Saint Thomases’ Hospital. A splendid dinner followed. I related as much as I could comfortably about our experiences with the Royal Naval Air Service, and about George Simpson. After dinner, Dorothy gave me a package. She invited me to open it when I returned to my hotel and said it contained several items that George had requested her to find for me. My return to France was delayed by problems with the ship on which I was to sail. Finally, I made it to Dunkirk. There the disembarkation officer helped me to find a telephone to arrange a drive back to Furnes. I had a long and serious chat with D’Albiac, our Records Officer, who had not received my telegram about the delay in sailing. Absolution received, I settled into a café to await a tender. 13 March 1917. Furnes, Belgium. We had a celebratory dinner in La Panne in honour of – wait for it – my old chum Huntington. Huntington has achieved ten Huns to his credit and been awarded the DSC. There is even talk of making him a flight commander. Huntington gave a stirring speech at the end of dinner, in which he thanked all of us for our support and vowed to continue taking the fight to the enemy. He even managed to work his beloved Eliza into the conversation, saying that decorations meant nothing to him – all he wants to do is make her proud of him. It seems that his last three claims have all been unwitnessed. Once the patrol breaks up and the pilots head home on their own, Huntington goes off to do battle with the enemy. Increasingly, his claims from these solitary quests go unquestioned. In the atmosphere of the wardroom, one does not question the integrity of one’s fellow officer. So there’s nothing for it except to smile and nod when Huntington is praised. Infuriatingly, he placed a hand on my shoulder whilst we were finishing the port and said, “Terribly sorry to have taken advantage of your leave to surpass your score, old boy.” Simpson and I have taken Reggie Soar into our plot. We have decided to head for La Panne on our first dud day and spend the afternoon putting it all together. I will share the contents of Dorothy’s package at that time. 21 March 1917. Furnes, Belgium. A busy week back with the squadron. Flew twice on the 14th, encountering a large group of Albatri whilst on a close offensive patrol near the coast. I managed to drive one down but did not see it hit the ground. On 15 March, we were to attack the rail yard south of Roulers, but as we crossed the lines at 11,000 feet we were attacked by a large formation of Halberstadt scouts. Our Tripes handle these machines rather comfortably. After twisting about the sky for a couple of minutes, the fight spread out and I spotted one of the brown Halberstadts turning behind a Triplane. I dropped in behind the Hun and gave it a long burst. The HA immediately began to trail black smoke, and then a bright tongue of orange flame snapped back from the cockpit. I silently hoped that I hit the pilot before the fire erupted. This victory over the Hun, however, was hard to miss and Simpson was able to confirm its fall. My score was up to eight. With the exception of Huntington, we all pretend not to count our scores. But dammit, I can’t help treating it as a competition. I added another Halberstadt to my bag on 18 March. A mixed group of Halberstadts and Albatri engaged us as we were climbing over our lines and preparing for another trip back to Roulers. This time I chased the HA down to nearly treetop level before finishing him off. Huntington, however, claimed another Halberstadt that morning – this one beyond question, so he had eleven to his credit and I had nine. Then on 19 March we were off to attack the Hun aerodrome at Ghistelles, which the Flemish call Gistel. We approached over the sea and turned inland for the attack. We were in squadron strength and our other flight was already beating up the aerodrome when a very large group of Albatri decided to interrupt the proceedings. We met several of them head on and tried to turn behind them. The Huns were faster and zoomed into high turns. One of them punched a few holes in my wings, but this time I was able to snap the Sopwith into a left turn and catch the HA as it began another climb. My rounds hit all about the pilot and I saw the enemy machine tumble out of control. A second HA passed in front of me, diving right-to-left. I was behind him in an instant and firing. Flames immediately began to pour from the engine of the Albatros and I watched it, a black machine with a white band around its fuselage, as it fell in flames directly over the enemy aerodrome. I claimed both Albatri, but the first was accepted only as driven down. Several of the fellows had seen my flamer over the aerodrome, so it was confirmed. Number ten at last! -

Please excuse me if I mentioned this before, but I would love to see the ability to transfer RFC/RNAS pilots from squadrons in France and Flanders back to the UK and vice versa. It would allow campaigns with periods of duty on Home Establishment.

-

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion

Albert, Wow! I'm really impressed by Edward's streak of victories. It has not taken him long to become the star of MFJ 1. For my part, I have been working from home on my laptop rather than from my office and apartment in town where my WOFF computer sits. I'll be moving it home in a week or two because health reasons will see me spending less time at the office. I'll have a lot of catching up to do. In the meanwhile, keep Edward's skin intact. Those Albatri will be on their way to you before long. Raine -

DiD IV Campaign - Flight reports & Player instructions

Raine replied to epower's topic in WOFF BH&H2 - General Discussion